This blog entry is a lengthy one. It has to be if I'm to tell the story as completely as I can.

Because of the title I've settled on, I feel a brief introduction is required.

You see, these crimes certainly involve more than three mothers and I've written about more than two abductions however, only three of the women and two of the abductions are directly linked.

There is just the one murder; that part of the title is accurate.

With that disclaimer out of the way .......

There has been much written about women entering the workforce during WWII, to take the place of the men who were off fighting the good fight, and rightfully so, but what about the children of these women?

I don't think we often hear about the resultant childcare crisis. Who would watch the children while the mothers were working?

It makes sense that, much like today, either or perhaps both sets of grandparents would step in to help but what if the grandparents also had full-time jobs or lived too far away to be of any practical assistance. Or what if they were deceased?

Some working mothers were forced to leave their children in the care of strangers. What a boon for nursemaids and nannies, I suppose, but what an opportunity for baby-snatchers.

The Jevahirian family of Detroit, Michigan unwittingly and tragically laid the groundwork for one such abduction in May 1943 when they advertised for a nursemaid to help look after 11 month old Paul, Jr.Twenty-three year old Paul Jevahirian, Sr. was serving as a Military Policeman, stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. His wife Alice, nineteen-years-old, had returned to work in March of 1943, employed full-time at a war plant.

Following Alice's return to work and Paul, Sr.'s induction in the Army, Paul, Jr. was left in the care of his paternal grandparents, Samuel and Elizabeth Jevahirian. The older couple lived at 2726 Chene Street.

Alice was living less than 10 minutes away, with her sister, Mrs. Irene Dodson at 6359 E.Lafayette Street.

Samuel (named Soukias at birth) and Elizabeth were naturalized citizens. Samuel was born in Turkey; Elizabeth came from Hungary. Both immigrated to the United States in 1918. Paul was the oldest of their 4 children.

The Jevahirian family was also known to use the last name "Diamondson" but for the purposes of this blog, I'll stick to Jevahirian.

Alice's own parents were no longer alive. Her mother Johanna had died on December 6, 1934, at the age of 37 years, from (and I'm quoting the death certificate) "right upper lobar pneumonia and portal cirrhosis." Alice's father Stanley, aged 47 years, died on August 10, 1941.

A housepainter by trade, Stanley Cherry died following a two story fall from a ladder. His death certificate records the cause of death as "Cardiac respiratory failure following fracture dislocation of cervical vertebrae with compression of cord."

Following Paul, Jr.'s abduction, only the very earliest newspapers articles reference some tension between Alice and

her in-laws. This discord apparently stemmed from Sam and Elizabeth's disapproval of the young couple's marriage.

According to Alice, Sam and Elizabeth "had another girl picked out for him."

Perhaps this accounts for Alice consenting to leave her son in their care but opting to live with her own sister? Or was there simply no room for another adult in the Jevahirian's home?

In 1943, Samuel Jevahirian was an electrical contractor with his own business, and his wife Elizabeth was employed by the Essex Wire Co.

No one adult or a combination of several could adequately look after Paul, Jr.. The decision was made to employ a nursemaid.

Mrs. Alice White, who must have seemed like a godsend, was hired on by Elizabeth Jevahirian to relieve the family's burden but six days later, on June 3, 1943, Mrs. White literally walked away with Paul, Jr. and she never came back.

This was the first time Mrs. White had been left alone with the boy.

Grandmother Elizabeth Jevahirian had stayed home from work for three days, to get better acquainted with Mrs. White and to be sure things would run smoothly, before finally having to return to her job.

Neighbors reported seeing Mrs. White leave the family's apartment the morning of June 3rd with Paul, Jr. in tow, around 11 AM.

Alice

Jevahirian wasn't made aware of the situation until 11:30 PM on the night

of the abduction. The last time Alice had spent time with her son was

four days prior and the visit had been very brief - just a quick "hello," "goodbye" and "I love you."

Paul, Sr. was not immediately contacted but it soon became abundantly clear that Mrs. White wasn't going to return and that the boy's father would need to be informed. Especially as the Detroit Free Press was already running articles about Paul, Jr.'s disappearance.

And while Mrs. White didn't leave the family entirely without hope, this was most likely a stalling tactic rather than a kindness.

On June 4th, a telegram from Mrs. White, originating from the Greyhound Bus Station, was received by Paul, Jr.'s grandparents.

The telegram, which had been sent not to the Jevaharian home but a nearby grocery store, read: "Sorry, won't be able to take care of Paul. My sister is dead. The baby is safe with a lady with whom I stay. She has your address. I will see you either tomorrow or Saturday."

What lady?

This mystery woman might have their address but the Jevahirians didn't have hers. And, now that they think about it, what did they really know about Mrs. White?

According to the grandmother, Mrs. White had refused to talk about her past life and didn't disclose where she had lived previously.

The only information the Jevahirians could tell the police was that Mrs. White was:

5 foot 6 inches tall, she weighed about 135 pounds, had (obviously) dyed red hair, blue-green eyes and was roughly forty years old. Mrs. White spoke with a southern drawl and seemed to have limited use of one arm ... but was it her left or her right?

Upon

receiving a frantic telegram from Alice, Paul, Sr. was granted

emergency leave. He returned to Detroit on June 9th.

"I can stay until June 22," Paul, Sr. told Detroit Free Press reporter Katherine Lynch. "I pray all the time that we'll find the baby before I have to leave. The awful thing is the waiting. We're afraid to go out, because some word might come."

Alice said, "I haven't any feeling about whether the baby's all right. I'm afraid to have."

As far as physical evidence which may help identify Mrs. White, The Detroit Free Press reported:

"Mrs. White, the family said, had no personal effects when she was employed, and left nothing behind except a cheap striped wash dress which she had bought this week. It was a size 16."

The police dusted the nursery for fingerprints and retrieved partial prints (two fingers only) from a bottle of hand lotion.

|

| Detroit Free Press (June 7, 1943) |

The FBI was unable to step in because Paul, Jr. had not been missing for the requisite 7 days nor had there been a ransom demand.

There also wasn't any proof that the child had been transported across state lines so the Lindbergh Law (in effect since 1932) wasn't applicable. However, the FBI's Special Investigation Squad followed the case closely and recorded any information that might lead to the child's recovery.

There was significant press coverage of the abduction and several tips came in, each one giving the Jevahirians hope, but none of them led to the recovery of their son:

- On June 6th, Ferndale (Michigan) resident Mrs. Naomi Condon, reported that Mrs. Alice White might have been a nursemaid who quit her employ a year ago. There was no proof that the two women were the same but police listened.

- Also on June 6th, a man, not identified by name to newspapers, contacted the Ypsilanti (Michigan) State Police because the description of Mrs. Alice White sounded like his mother, also named Alice.

His mother, who worked in Detroit homes, was a drug addict and was already known to Federal Narcotics Bureau.

The man reported that a taxi cab pulled up outside of his home the evening of the abduction, or perhaps it was the following night, but nobody exited the vehicle. It was his mother's habit to not approach the house if she could see her son already had visitors and he was certainly entertaining friends that evening.

Detroit police asked the Ypsilanti State Police to check all the taxicab drivers in the city to see if any of them drove a woman to that address.

- On June 9th, the Board of Wayne County Supervisors offered a $250 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Paul, Jr.'s kidnapper.

- On June 15th, the Detroit Police Dept. offered an additional $250 for information leading to Mrs. White's apprehension.

- On July 1st, 10,000 circulars bearing Paul, Jr.'s likeness began to be widely distributed throughout North America and even Central America. Paul was described as:

"weighing between 25 and 30 pounds, is fair skinned, with blond hair, blue eyes and a noticeable lump on the bridge of his nose. He has four upper and four lower front teeth."

In the days before DNA swabs, footprint images inked at the time of Paul, Jr.'s birth, would be the Jevahirian's best tool to match any child suspected of being their son. Unfortunately, Paul, Jr.'s set of prints were smudged. This would be a problem throughout the search.

A second set of footprint impressions, taken by Paul, Sr. for his son's baby book, proved helpful but there were issues with those as well.

|

| Detroit Free Press (Nov. 22, 1944) |

Thomas A. Dwyer, Detroit police identification bureau head, was highly critical of the footprinting work being done by the Highland Park General Hospital. Dwyer felt the over-inking of Paul, Jr.'s feet resulted in "blurred and distorted" prints which would make positive identification impossible.

In November 1944, Thomas Dwyer took it upon himself to visit the hospital and instruct nurses in the proper technique.

Paul, Sr., who was stationed in Texas at the time of his son's abduction, eventually obtained a transfer to Selfridge Field in Harrison Township, Michigan, roughly 30 miles northeast of his parents house.

The Jevahirians continued to look for Paul, Jr. and/or Alice White.

In addition to impulsively peeking into any passing baby carriages and following women who looked Mrs. White, the Jevahirians worked hard at keeping their son's name in the newspaper and they were a regular presence at Police Headquarters.

|

| D.F.P. - (March 8, 1946) |

Even joyous occasions such as the birth of a second child, their daughter Marlene, became an opportunity to remind the public that Paul, Jr. was still missing.

A photo of mother and daughter was printed in the Detroit Free Press on October 15, 1944.

"If the Free Press publishes her picture, someone may remember seeing a boy baby who looked like her," the mother said with tears in her eyes. "I suppose he looks very different. He'd be walking and talking by now."

Alice also told the reporter she was reluctant to leave Marlene alone for even a minute. Who could blame her?

"Just being away from her frightens me," she said. "Even when I know relatives are watching her, I'm scared. I have to keep reassuring myself that she's safe."

A third child, their daughter Lois, joined the family in in 1945. A photo of Alice and the girls appeared in the Detroit Press on August 8, 1948 above the headline

"No Trace: Parents Still Mourn Kidnapped Infant."

|

| Detroit Free Press (August 8, 1948) |

Alice's reported impressions of Mrs. White would mutate over the years.

|

| D.F.P. (June 3, 1944) |

In an article published by the Detroit Free Press on June 3, 1944, the one year anniversary of Paul's abduction, contained this passage:

They remember 'Alice White' well as five feet six inches tall, about 35 years old, with a long thin face, blue-green eyes, heavy-lensed glasses, speaking with a slight southern drawl. They did not know her background, but remember that she seemed to have money and "spoke in a cultured way." It did seem odd, they recalled, that she worked as a nursemaid but "she was so good with the baby."

At the time of the above interview, Paul was home on a 60 day furlough.

"I guess the Army figures I'm no good to them as long as our baby is gone."

In 1948, Alice told the Detroit Free Press that she had intended to fire Mrs. White on June 4th, one day after her son was stolen.

"Mrs. Jevahirian could not endure coming home every evening and finding Paul crying. At best, it did not indicate a fondness for children on the nurse's part."

Throughout the years, whenever there was an account of either a suspicious private adoption, an abandoned baby or an abduction similar to their son's, the Jevahirians were there.

One

notable kidnapping in which Alice became interested was the 1944 abduction of four-month-old Robert James King from his home at 11431 Minden Avenue. This address was a quick 15 minute drive from 2726 Chene Street.

On the evening of Saturday, September 30, 1944, Clarence and Katherine King left their four-month-old son in the care of their newly-hired housemaid Helen Rosman. They wanted to have a belated celebration of Mr. King's birthday by going to the movies so earlier in the week they asked Helen if she would be willing to watch Bobby for several hours on Saturday.

Their eldest son, seventeen-year-old Emory, a student at Denby High School, was out of the house that evening as well, attending a party for a serviceman buddy. This was the first time Helen would be left alone with Bobby.

|

| D.F.P. (Oct. 2, 1944) |

They immediately called the police.

Kidnapping for profit didn't seem likely. Mr. King, as an assistant sales manager for the Benjamin Rich Realty Company, was, as the Detroit Free Press described him, "a man of modest means."

Miss Rosman had been employed by the Mr. & Mrs. King only one week earlier, on September 23rd (Clarence's 40th birthday). Helen had answered an ad placed in a Detroit newspaper. The Kings were looking for a high school girl to do house work and care for a baby during the after school hours.

Unlike "Alice White," when Helen applied for the position she was very forthcoming with many personal details.

Helen told the Kings she lived with her parents on E. Arizona Street; her father was employed by Ford Motors; Helen's mother disapproved of her having boyfriends but she did have a sweetheart who went to Cooley High School; she was senior student at Northern High School and planned to study child psychology at the University of Michigan after graduation.

Helen provided but reclaimed, a letter of reference from a former employer, a Detroit doctor who was currently in the military.

Mrs. King, thirty-six-years old, was so impressed that she didn't bother to check up on the validity of these "facts."

As the week progressed, Mrs. King found Helen to be a competent housekeeper and thought the girl was particularly good at caring for little Bobby. Helen reported for work at 2 PM and usually left the King house each evening at 8 PM.

After the disappearance of Bobby, police detectives did a house to house on E. Arizona Street and couldn't find anyone who knew the Rosman family. They also checked with residents of E. Philadelphia Street because the Kings recalled Helen saying she had also lived there at one time. The principal of Northern High School was unable to locate a record for Helen Rosman.

A description of "Helen Rosman" was widely circulated:

"Eighteen years old, but looks a few years older. She is five feet six inches tall and weighs about 140 pounds. She has a dark complexion, dark eyes, thick lips, and dark, kinky hair. Spoke with a slight accent, wore rimless glasses and claimed to be of French-Jewish extraction. When last seen she was wearing a red skirt, a blue-green blouse, black shoes and a full-length, black, form-fitting coat."

Despite Helen's claims of a Jewish-French background, the police wondered if perhaps she had "some Negro blood."

Several leads came in:

- A DSR (Department of Street Railways) bus driver, Oscar Edwards, told police he had picked up a young girl who matched that description at 9:14 PM Saturday night. She was carrying a baby wrapped in a pink blanket. She boarded the bus at the corner of Gunston Street and E. McNichols Road. He had let her off at McNichols and Gratiot Avenue.

- A woman working the information desk at the Union Depot, Miss Betty Atkinson, told police a young girl carrying a baby and matching that description came to her counter at 9:30 AM Sunday, in the company of two men, and asked when the next train to Pittsburgh would be leaving. It would be a 3 hours wait, the train was leaving at 12:30 PM.

- A woman answering Helen's description had entered a Unionville, Michigan restaurant the morning of Sunday, Oct 1st and asked a waitress to heat the baby's bottle. The woman spoke with a southern accent and was in the company of two men. They left in a car heading east.

Every lead had to be investigated. The detectives assumed that the abduction was planned in advance. They rationalized that Helen had left the King household shortly after the couple went out for the evening. Helen had a four hour head start before the Kings called the police.

|

| Detroit Free Press ( Oct. 3, 1944) |

Copies of Bobby's footprints would be sent to police departments throughout the country for comparison.

Police also heard from Mrs. Helen Reid, of 2100 Junction Avenue.

On Labor Day of 1944, Mrs. Reid had advertised for a middle-aged woman to care for her child. A woman identifying herself "Helen Rosman" and giving her age as forty-years-old had phoned Mrs. Reid to apply for the job.

When Mrs. Reid met the woman she realized Helen was much younger than she said and Mrs. Reid refused to hire her. It didn't help Helen's cause that the address she had given as her home address was a location on Livernois Avenue. Mrs. Reid realized that was a gas station.

As was the case in the abduction of Paul Jevahirian, Jr., the FBI was prohibited from entering the investigation until October 8th, 7 days after the investigation had begun.

The Police Department's Investigation Bureau found a single thumb print on a drinking glass in the King home and they believed it be the kidnapper's print. It was Helen who had washed the dinner dishes that evening.

Wayne County authorities authorized a $500 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the kidnapper.

Druggists were asked to pay attention to anyone buying the specific ingredients little Bobby needed for his colic.

|

| Karl Larsen's sketch |

The Detroit Free Press sent portrait artist Karl Larsen to the King home so he could work with Katherine King to draw a sketch of "Helen."

On October 4th, the likeness was printed on the newspaper's front page.

An open letter to "Helen Rosman," penned by Detroit Free Press staff writer Kathleen Lynch, appeared on the front page of the newspaper's Thursday, October 5th edition, urging the young woman to do the right thing - return the baby to his rightful parents.

The author tells Helen that Mrs. King has been destroyed by the loss of her child -

You know what a frail little woman she is. She hasn't slept much since you left. She talks and moves jerkily. Her voice is almost a whisper. There are dark circles under her eyes.

She sits and stares into space a lot of the time, and she keeps remembering that she trusted you because you were so fond of the baby.

But your love for the baby, Helen, is less than hers, however much you love him. Remember that he is her own son.

You don't want to give Robert up now. Think how you would feel if he were your own baby. You would never get over losing him.

No doubt, Alice Jevahirian read this same newspaper and thought of Paul, Jr - missing since June 3, 1943.

On Saturday, October 7th, 1944, Mrs. King answered the telephone and listened to a weeping woman saying, "Bobby is well but I can't bring him back."

Helen's physical description did not, in any way, match "Alice White" but maybe there was a sophisticated baby-snatching ring operating in the Chicago area?

Alice Jevahirian met with Katherine King on October 7th to compare notes.

|

| Detroit Free Press (Oct. 7, 1944) |

When it quickly became evident that the cases were not related, the two women could do little except cry on each others shoulders.

While Alice most likely followed the case with great interest and empathy, it seemed unlikely that a resolution in this case would lead to the recovery of her own son.

|

| George D. McKee |

McKee, a janitor at the Federal Building in Detroit, was at the St. Stephen A.M.E. Church (6000 Stanford St*), when he noticed a light-skinned, blue-eyed baby in the arms of Mrs. Eleanor Smith.

(*now John E. Hunter Drive)

Knowing it would be highly unlikely for a blue-eyed baby to be born to two black parents, McKee phoned a tip into the Detroit Times newspaper. The newspaper contacted the police. The date was Sunday, October 8th, 1944.

Mrs. Smith, 32 -years-old, had been a member of the church's congregation since 1939. She'd previously sang in the choir and had even taught a Sunday school class in the junior department. The hint of a southern accent could be attributed to the fact that Eleanor was born and raised in Arkansas.

.jpg) |

| Eugene Smith |

Eugene said Eleanor, his wife of four years, announced the pregnancy in June.

In July, Eleanor left Detroit for Metropolis, Illinois to visit her mother.

According to Eleanor, before she reached her destination, the baby was born two months prematurely in The Wesley Memorial Hospital in Chicago. When Eleanor returned home, it was without their son.

"Eugene, Jr." was still a patient at the Chicago hospital. Eleanor's cousin would be bringing their son to Detroit by train as soon as he was healthy enough to travel. That joyous day was September 30th, 1944.

Eugene said Eleanor insisted that she go alone to the train station to meet her cousin. He didn't see the light-skinned, blue-eyed child until 11:30 that night. He was immediately suspicious, as was Eugene's mother.

Eugene began making quiet inquiries with the Chicago hospital; his suspicions were confirmed. There was no record of Eleanor giving birth at the hospital but Eugene loved his wife too much to call the police.

George D. McKee, however had no such reservations.

|

| Detroit Free Press (Oct. 12, 1944) |

Eleanor was reluctant to show them her baby but, when pressed, she allowed them a quick peek and made a point of showing them a grayish "birthmark" on the sleeping child's forehead.

"Your baby didn't have that," Eleanor informed them.

Mr. King insisted the Smith baby's feet and Eleanor's fingerprints be inked for comparison. This happened at 6 PM. By 6:30, Inspector George McLellan was satisfied that the prints didn't match and everyone left. Detective Paul A. Wencel hadn't even entered the house.

Emory King told police "I know there can't be two women who look as much alike as that."

Remarkably, the police didn't detain Eleanor Smith or even leave an officer at the scene to assure she didn't disappear....again.

|

| a side-by-side comparison of Eleanor King and the Karl Larsen sketch of "Helen Rosman" |

The set of finger and foot prints were turned over to the department head, Inspector Thomas Dwyer. Dwyer left them on his desk and went home.

Police Commissioner John F. Ballenger had been informed that the prints didn't match; he too went home.

Hours later, Detective John Orlikowski, an identification officer who was working late, decided to enlarge the prints and have a closer look.

Orlikowski later admitted it was more for something to do on a slow night than any real instinct. The detective was astonished to see a match of both the footprints and the thumbprint impression from the drinking glass.

|

| D.F.P. (Oct. 12, 1944) |

Only then, at 12:10 AM on October 11th, did police return to arrest Eleanor Smith. Mrs. Smith continued to insist she did not steal another woman's baby.

October 12th newspapers carried the announcement by police of Mrs. Smith's full confession.

Commissioner Ballenger hadn't heard the good news until 7 AM that morning. He quickly launched an investigation into the "bungling" by the detectives. All involved denied any culpability.

On October 13th, newspapers reported on Mrs. Smith's staunch denial of the confession and the fact that she was on a hunger strike.

Eleanor was visited in prison by her pastor, the Rev. W.E. Walker, on Saturday October 14th; he brought her a basket of fruit and the hunger strike ended.

|

| D.F.P. (Oct. 26, 1944) |

"I'm proud of my family and my husband and my baby and myself.

"I've never done a thing in my life to be ashamed of. I've never been arrested or done a wrong thing since I was born. My conscience doesn't bother me."

Eugene, Sr. confirmed that his wife had suffered a miscarriage early in their marriage and he said she had been quite grief-stricken at the time.

.jpg) |

| D.F.P. (Oct 12, 1944) |

The "birthmark" was subsequently wiped off by Mrs. King with a warm washcloth. Mrs. King also had to wipe away a layer or two of sun tan oil.

A sympathetic Katherine King told reporters, "I know she (Eleanor) took Bobby because she wanted a baby. I suppose her desire for a child had unbalanced her. She has caused me terrible grief but I can't help feeling sorry for her."

Mrs. King told a Herald Press reporter that she attributed his rescue to his blue eyes.

"We can thank God for that," she sighed with relief yesterday as the child slept in his crib. "Otherwise he might never have been found."

At her October 13, 1944 arraignment on kidnapping charges, Eleanor Smith entered a plea of not guilty and she was held on $25,000 bond.

.jpg) |

| D.F.P. (Oct. 13, 1944) |

Two days later, The Detroit Free Press revealed that they had tracked down Eleanor's 1938 divorce decree from husband James Barnett and the document stated no children had been born to the couple during the marriage.

Eleanor's statement to the police following her October 11th arrest, aka her confession, was later presented in court.

The specifics of Eleanor's October 11th confession were printed in the Detroit Free Press on October 26, 1944. This included news that she had delivered a still-born child in her cousin's Chicago home on June 20th:

Mrs. Smith related, according to the statement, that she had left Detroit intending to visit her mother in Metropolis, Ill.

En route, the statement declared, she became ill before the train reached Chicago. She left the train when it reached that city and went to the home of a cousin, Mrs. Ossie Harris.

The dead child was born a few hours after her arrival, the statement continued, with a midwife who lived in the same building in attendance.

Before her return to Detroit July 5, the statement said, Mrs. Smith had been treated under an assumed name and as a day patient at the Wesley Memorial Hospital.

Despite the above remarks, Eleanor Smith continued to insist Bobby King was her child.

At a hearing before Judge Gerald Groat, Mrs. Leon Grant, a neighbor of the Smith family, testified that she had spoken with Eleanor on September 30th and "Mrs. Smith told me she was to meet her cousin who would bring the baby born three months previously to her in Chicago." This, the prosecution felt, showed intent and planning by Eleanor to steal the child.

"The next day I saw the baby for the first time," Mrs. Grant continued. "I noticed that it had a light complexion, but I didn't doubt it was Mrs. Smith's baby."

On December 30, 1944, a three person sanity commission was appointed, at the request of Eleanor's attorneys, to determine their defendant's mental state.

On January 19, 1945, Eleanor was deemed unfit and suffering from a mental disorder. She was committed to Ionia State Hospital aka The Michigan State Asylum.

|

| Ionia State Hospital (1883-1977) (demolished) |

On June 25, 1945, Eugene Smith filed for divorce, citing "cruelty." On October 8, 1945, the divorce became final. On January 6, 1946, Eugene, then 36, married 18-year-old Marie Lavern Snyder.

I cannot find any evidence of a trial, which would have taken place upon Eleanor being declared "fit for trial." This doesn't necessarily mean she was an inmate of Ionia State Hospital until her death.

I'm not able to verify either exactly when Eleanor died. One Ancestry family tree lists a date of death for Eleanor Tyson (her maiden name) as February 11, 1993 but the woman's date of birth doesn't match Eleanor's actual birth certificate - which I've seen.

On November 30, 1944, Detective John Orlikowski was given a belated citation for his efforts in identifying the two sets of prints. A few weeks later, Orlikowski, citing "eye strain," asked for a transfer to the Missing Persons Bureau.

Veteran police reporters believed Inspector Thomas Dwyer, who was bitter over the reprimand he had received for his own mishandling of the fingerprint evidence, was at the heart of Orlikowski's request.

Orlikowski's desire to move on was good news for three other departments who made it known they'd be happy to have him.

The $500 reward offered by Wayne County for Bobby King's return was split between George D. McKee and Claude Bender (whoever he is).

The Kings had their happy ending but what about the Jevahirians? Would they be as fortunate?

|

| Detroit Free Press (Oct. 19, 1944) |

On October 7, 1944 (one week after Bobby King was abducted), another child was stolen in a manner very similar to Paul, Jr.'s abduction.

While this happened one state to the south and 220 miles away from the Jevahrian's home, police and reporters quickly made the connection.

Here are the facts:

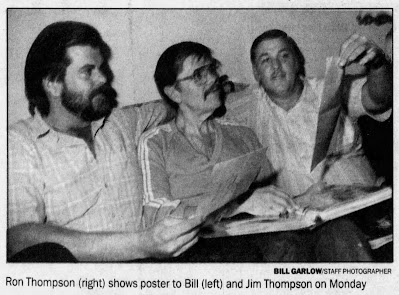

Ronald Eugene Thompson, 20-months-old, had been whisked away from his Dayton, Ohio home by his recently hired nanny "Mrs. Mary Wilkey." *Quick note - the woman's last name has also been spelled "Wilkie" but, wanting to keep it consistent, I will only use the "Wilkey" spelling.

Ronnie's father, Arthur C. Thompson, a 35-year-old Army private, was serving overseas in France at the time of the abduction.

|

| Dayton Daily News (Oct. 8, 1944) |

Mary Wilkey came to be employed by Anna Thompson after answering this help wanted ad which appeared in the Dayton Herald newspaper on October 3rd.:

Woman to care for small child in exchange for home and wages; mother registered nurse. MA 1937

Anna had already been sharing her apartment at 210 Klee Street for a brief period of time with Mrs. Elizabeth (Betty) Elworth, aged 24, a newlywed woman who's husband Raymond was likewise serving overseas.

However, Betty had chosen to move out three weeks prior to the abduction because she had become ill and was afraid to pass the cold along to Ronnie.

"Ronnie got the cold, anyway," Mrs. Elworth said bitterly. "I shouldn't have given up my job and this never would have happened."

Mary Wilkey entered their lives at 8 PM on Friday October 6, 1944. The interview went well. Ronnie seemed to like Mrs. Wilkey and she liked him.

Mary Wilkey explained that she was a widow who had raised three boys of her own; all three sons were currently in the military. Mary said she had lived in Dayton 20 years earlier and had come back to Dayton now to visit with one of her sons and his wife while he was on furlough. Mary said she would be ready to start work the following day.

The next morning, as promised, Mrs. Wilkey knocked on the door of 128 McClure Street, the home of Ronnie's maternal grandparents.

Mrs. Wilkey suggested she take Ronnie for a haircut and he went along without a complaint.

Days after his abduction, Anna Thompson told a reporter from the Dayton Daily News about the last time she had seen her son, at 9:30 AM Saturday, October 7th:

Days after his abduction, Anna Thompson told a reporter from the Dayton Daily News about the last time she had seen her son, at 9:30 AM Saturday, October 7th:

"The woman was going to take him for a walk. Usually, he doesn't want to go with strangers, even with his grandmother, if I am around, so I ducked into the house, and she led him away. I peeked out the window to see how they were getting along, and I saw them at the corner, crossing the street. He was quite excited, because a horse was passing by. He look so tiny, and so eager. He just has to come back."

Mary Wilkey never returned.

Anna Thompson grew increasingly anxious and at 10:45 she left the house to find the pair.

Anna checked in with two barber shops. No luck.

"I thought maybe the were lost, so I drove around," Anna said, "but there was no sign of them. By this time I was getting nervous. After noon, one of my brothers drove me down to the bus depot. I went in, looked all over for them.

"But I didn't say a word to anyone in the station. Now I realize that if I had just asked someone there ..."

They drove back home.

At 2:45 PM that day the Wakers received a Western Union telegram from Mrs. Wilkey:

"We phoned. Unable to reach you. I phoned this friend I spoke of (the one 20 miles away). She has a fracture and would be unable to bring my baggage over. The nurse is taking care of Ronnie so I didn't change your plans. We will be there at 6 P.M. today. I don't think it will be necessary. If delayed we will be there Monday in the daytime. Everything is ok. Don't worry. Sorry."

They phoned the police immediately.

Police confirmed that Mary Wilkey and Ronnie had actually appeared at one of the two the barber shop Anna had checked, twice. The barber didn't recall their pressence until later. On each occasion the shop was crowded and Mary told the barber she would try again later.

Detectives traced the telegram as being relayed from a public phone at the Greyhound bus station. The message was filed at 12:59 PM, with instructions that it be delivered between 1:15 and 2 PM. Only two buses leave the station during that hour, one to Columbus and other points east and the other south, to Lexington, KY, and other points.

The two hour delay in delivering the telegram stemmed from the fact that the last name of Waker was misspelled as "Walker."

On October 11th, the Dayton police initiated an eight state alert for "Mary Wilkey."

| ||||

| A sketch of "Mary Wilkey" by Dayton Daily News art director Homer Hacker |

Detectives

in nearby Detroit were quick to

see the similarities between the kidnapping of Ronnie Thompson and their own open investigation into the abduction of Paul Jevahirian, Jr.

Detectives

in nearby Detroit were quick to

see the similarities between the kidnapping of Ronnie Thompson and their own open investigation into the abduction of Paul Jevahirian, Jr.

Frank C. Selvidge, the Jevahirian's private detective,

also took note and felt there was a connection. Selvidge traveled to

Dayton to meet with the police detectives handling the Thompson case and

he made a very convincing argument to support that theory.

Four thousand circulars were printed for distribution throughout the United States and parts of Canada.

.jpg) |

| Dayton Herlad (Oct. 13, 1944) |

Here is a recounting of the attempt in an article from the October 13, 1944 (Friday) edition of the Dayton Herald:

Betty had left the apartment Wednesday evening for the first time to go to a movie, and had returned around 2 a.m. yesterday

She had told Mrs. Thompson she was writing a letter to her husband shortly after she came home, and went into the bathroom to take a few of the sleeping tablets, apparently to induce sleep. She started to make a telephone call and fell to the floor. Mrs. Thompson heard the noise and carried the girl to the davenport, where she remained in a deep sleep until 1 p.m. yesterday.

About 2 p.m. she rose, went to the bathroom again, and swallowed a handful of the tablets before Mrs. Thompson could stop her. Mrs. Thompson, night nurse supervisor of St. Ann's hospital, immediately called an ambulance and took the girl to St. Elizabeth Hospital. Attendants said the victim would "sleep off" the effects of the tablets until today, but would suffer no ill results after treatment.

Betty left behind a barely legible note, dated "Oct. 12, 3:37 a.m.:

"Dearest Sweetheart,

Remember I love you and God keep you safe. Perhaps this is wrong but my life may bring back Anna Mary's little baby. I hope it isn't in vain. If I had left her this wouldn't have happened."

Anyone desperate for clues as to Ronnie's whereabouts might have thought Betty was admitting to having played a part in the child's abduction when they saw she'd written "If I had left her this wouldn't have happened."

However, the police investigated this angle and Chief R.F. Wurstner determined Betty was innocent. He believed Betty had meant to write "If I had not left her ..." and simply omitted the word "not." This sentiment mirrored her previous comment.

Betty was treated at St. Elizabeth Hospital and released into the care of her in-laws.

As was the case with Paul, Jr.'s abduction, Ronnie Thompson's father was the last one to know his son was missing. Word didn't reach Pvt. Arthur C. Thompson until October 28, 1944 - three weeks after his son was taken.

The Thompson family, like the Jevahirians, had their own share of false leads and crushing disappointments.A sleeping, half-starved and naked young boy, abandoned in a Seattle hotel was found by a maid on November 6, 1944. It was possible this was Ronnie Thompson.

Baggage containing men's and women's clothing had also been found in the room.

|

| AP Wirephoto of "Jackie" |

A photo of the boy, who called himself "Jackie," was sent via Acme telephoto to Fostoria, Ohio (not Dayton) on November 9th. Jackie did bear a resemblance to Ronnie.

Even Grandma Waker said, "If you cover up the shoulders in this picture it certainly looks like Ronnie. And you can't tell exactly, since the circular picture of Ronnie, enlarged, looks older than Ronnie does."

Anna Thompson's hopes were dashed when she read the description of "Jackie." This boy, in addition to being 3-years-old had blue eyes - not brown. Also, she could see in the photo that the child's ears were too large and his face too broad for it to be Ronnie.

Jackie's real mother, Neta Beckwith, saw the same photo in her Seattle newspaper and recognizing that to be her son, phoned the police.

She had separated from William A. Beckwith earlier in the year, and although Neta had been awarded custody of their son after the separation. Neta Beckwith told police she'd turned their son over to William because she did not have sufficient room for him at her residence.

William A. Beckwith, aged 29, was arrested when he walked into the Seattle hotel. He claimed his son's name was William L. Beckwith not Jackie and that he had left his son in the care of an 18-year-old "nanny."

Curiously, when the nanny registered at the hotel with "Jackie" at 3 PM on Monday she presented herself as "Mrs. James Yost" and said the boy was her nephew. She checked in, then walked out - leaving Jackie and the luggage behind.

She returned at 11 PM and when "Ms. Yost" learned that police had Jackie in custody, she took off; without retrieving her luggage.

Police suspected Mr. Beckwith was attempting to cover up the true nature of his relationship with "Mrs. James Yost."

Both Mr. and Mrs. Beckwith were charged with "contributing to the delinquency of a minor."

This seems a little unfair to Neta Beckwith since she wasn't involved in the incident at the hotel. However, she was the legal guardian for her son.

Trouble with the law was nothing new to William A. Beckwith.

William was arrested in December 1942 for failure to make child support payments to his first wife, Winifred.

.jpg) |

| Seattle Star (Dec. 11, 1942) |

Under the terms of the 1939 divorce decree, William was to pay Winifred $25 a month in child support. At the time of his 1942 arrest, William owed Winifred $1072.

William had married his second wife, Neta on March 11, 1941 and they had started family of their own.

On December 11, 1942, reacting to the predicament he'd found himself in, William said, "I was all set to take my first wife to lunch after court - but all of the sudden the judge makes a decision. And look what happens to me ... I'm in jail.

"I had no idea that I would end up in jail yesterday when I started out for court. My former wife and I have been good friends and we were going to have lunch together after the court hearing. But we ate alone ... me in jail.

"I don't know how they can expect me to pay all of this back money for my two daughters and still support my son," William mused.

After serving one week of his six month sentence, William A. Beckwith agreed to pay Winifred $100 in cash and he promised to keep up with the $25 support payments.

"I sure don't like jail," he said. "I guess I'll have to get a better job now that the one I had - because supporting two families takes a lot of money."

Whatever new personal drama awaited the Beckwith family, it now meant nothing to the Thompsons.

Mrs. Thompson had been in Fostoria when the photo of "Jackie" came through because she was pursuing another lead. There was a tip about a man with long reddish brown hair who might actually be a woman in disguise.

This individual, claiming to be an Indian "herb doctor," had appeared in Fostoria on Thursday, November 2nd and left his car with a friend for repairs. He was due back on Thursday the 9th.

Mrs. Thompson had driven 2 hours on the hope that this crazy lead panned out - it did not.On November 10, 1944, Alice Jevahirian and Anna Thompson spoke over the telephone for 20 minutes.

Alice asked if "Mary Wilkey" had freckles across her nose and Anna confirmed she did.

They both recalled their nursemaid mentioning she would be able to go for a ride in a friend's car from time to time and asked if would be alright to take the baby along.

The more they talked, the more the two women were convinced they had lost their son to the same woman.

In mid-November 1944, the Jevahrians waited to hear if Paul, Jr.'s smudged footprints matched one of two babies abandoned in Dayton, Ohio. There was no match.

On December 15, 1944, Pvt. Arthur Thompson suffered a nervous breakdown and spent months in a series of hospitals in France, England and finally Tennessee.

Finally, on March 19, 1945, Arthur returned to Dayton for a 30 day furlough. His first stop was Police Headquarters. When the furlough ended, Arthur boarded a train that would take him back to the Army hospital in Tennessee. |

| Daily News (Aug. 26, 1945) |

Apparently, Alice was looking over a vacant room to rent at a boarding house at 97 Winder Street in Detroit when she found a small photo left behind by a previous tenant. Alice was in the company of an unnamed friend at the time, so perhaps it was her friend who was in need of lodging.

.jpg) |

| D.F.P. (March 14, 1946) |

Not trusting her own eyes, especially as she herself had only seen Mrs. White once ... nearly three years ago, Alice Jevahirian showed the photo to her mother-in-law, Elizabeth.

"That's Alice White," the older woman exclaimed. "I've looked at hundreds of pictures and the minute I saw this one I knew it was Alice. If it isn't her, it most certainly must be her twin sister."

Mrs. Mildred Martin, an employee of a dress shop in Detroit who had seen Mrs. White daily during the week before the abduction also identified the picture as "Alice White or a girl who bears an amazing resemblance to her."

The next person who needed to see the snapshot was Mrs. Anna Thompson. In exchange for an exclusive, a reporter from the Dayton Daily News was happy to oblige. "It resembles her very much," Anna said."It's the closest resemblance to her I have ever seen."

She added, "I never saw Mary Wilkey smile but I'm sure that is the way she would look. The resemblance is remarkable. The woman in the picture has good teeth and that is one of the things I remember about Mrs. Wilkey."

The apartment's previous tenant was "Howard Simpson," a man who had occupied the room from November 9-23, 1945. Other tenants of the house said the woman was a friend of Howard's.

It was theorized that "Howard Simpson" was an alias because, according to a Detroit News reporter, "people living at that apartment seldom used their correct names."

The photo ran in several newspapers with an appeal for the public to help identify this woman.

I don't know if either "Alice White" or "Mary Wilkey" were concerned about the publication of that snapshot but 18-year-old Mrs. Bernadine Ward of Port Huron, Michigan was certainly nervous.

|

| D.F.P. (March 15, 1946) |

Mrs. Ward said she had given the snapshot, taken at a "penny arcade" a year ago, to a boy living at the room house on Winder.

"She doesn't look like a girl of 18 in the picture," Anna Thompson said.

It was another crushing disappointment but neither family was willing to abandon hope. The Thompson family was in the same predicament as the Jevahirians - following every lead and keeping those footprint impressions close by.

For the Thompson family, another glimmer of hope arose in October 1949.

Six-year-old William "Tommy" O'Neill, who had been a ward of Michigan state since September 1947, was revealed to be a possible a match for Ronnie Thompson.

Tommy spoke no English when he entered the system.

According to a series of articles appearing in the October 14 & 15, 1949 editions of Ohio's Journal Herald, Tommy had been living with a wandering Mexican family that eventually settled in Lansing, Michigan.

When George Garcia filed for public assistance in July 1947, the social worker thought it odd that a blonde-haired white boy was living with the Garcia family. Tommy was removed from the Garcia's abode and housed in the Ann Arbor Children's Institute until his placement in a foster home.

In late September 1949, newspaper articles recounting Ronnie Thompson's abduction and the fact that he was still missing began appearing in newspapers nationwide.

Tommy O'Neill's foster parents, Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Foote of Hickory Corners, Michigan, saw the article and thought there was a chance that Tommy could be Ronnie Thompson so they made a phone call and Mrs. Thompson made plans to travel to Michigan.

Tommy apparently took it all in his stride and when he met Anna Thompson he told her "I want to go home with you."Arrangements were made for Anna to meet Mrs. Margaret Cooper Hart, who claimed to be Tommy's birth mother, and Mrs. Rae, a woman who had acted as a nursemaid for Tommy for a period of time when he was younger. Neither of them was "Mary Wilkey."

Mrs. Hart said that she had since remarried and refused to disclose her new last name to Mrs. Thompson. However, she did reveal something of Tommy's background.

I imagine the complete story is far more complicated, but here is a summation provided by Dayton, Ohio's Journal Herald newspaper on October 15, 1949:

Mrs. Hart said Tommy's real name was William Hart. He had been born in Toledo on January 1, 1943. When Mrs. Hart registered the birth she opted to use her daughter's last name of O'Neill rather than her own because she was not living with her husband at the time.

The Ohio Bureau of Statistics reported a record of a William Thomas O'Neill being born to James & Margaret Cooper O'Neill on January 1, 1943.

Mrs. Hart eventually handed her son over to her sister. When the sister tired of Tommy she gave him to the Garcia family.

WTF?

When doctors wanted some of Tommy's hair to compare with Ronnie's, the youngster pulled out several strands himself. It was an unnecessary move, according to Michigan State Police, because a comparison of the hairs would not prove anything.

Fingerprints taken from some of Ronnie's playthings did not match Tommy's fingerprints but it was an accepted fact that Ronnie's fingerprints, lifted 5 years ago, were only partial prints.

Anna felt there was a strong enough physical resemblance between the two boys that she pushed for additional testing.

Tommy's feet were inked so that the experts could compare the impressions with those of Ronnie.

.jpg) |

| AP Wirephoto (Oct. 14, 1949) |

Blood samples were taken from Tommy, Anna, Arthur and the Thompsons's two others sons, James & Robert (born in 1945 & 1947, respectively).

|

| The Journal Herald (Oct. 14, 1949) |

The blood comparison tests wouldn't prove that Tommy O'Neill was Ronnie Thompson but they could prove a familial connection.

Twelve hours later, Dr. Charles Cotterman, a nationally famous geneticist, had his results.

Detective Farrell Babcock had to deliver the bad news - Tommy O'Neill was not Ronnie Thompson.

Another disappointment.

Anna and Arthur went back to their hotel. A chartered plane returned them to Dayton.

|

| The Journal Herald (Oct. 15, 1949) |

There was some speculation in Michigan newspapers that the Thompson family would move to adopt Tommy, despite the negative results, but this wasn't in the cards. Even before the Thompsons left Dayton, another family had started the necessary paperwork to adopt Tommy themselves.

"I'm broken-hearted," said Anna. "I feel in my heart that some time God will return my Ronnie."

Anna's faith in God was not misplaced but it would be several more years, interspersed with more dashed hopes, before both the Thompson and the Jevahirians would learn what happened to their sons.

And it would take another family's tragedy to bring forth the truth.

On Monday, September 25, 1950, Lois Tipp, the 39-year-old owner and operator of the Woodside Screw Ball Inn, informed two Tampa, Florida newspapers that her eight-year-old son, Robert A. Tipp II was missing and that the kidnappers had also stolen $2,000 in cash.

|

| Tampa Times (9/25/1950) |

The newspaper editor suggested Mrs. Tipp contact the police but Lois said she was reluctant to do so because she worried the kidnappers would harm her son if the police became involved.

Lois ended the phone call but rang again later to say she had contacted the FBI. A Tribune reporter followed up on this with his own call to the FBI. Apparently, a woman had just called to ask if the FBI handled kidnappings but she gave no further information before hanging up.

On September 25, 1950, The Tampa Times ran the story on their front page. There was a photo of Robert A. Tipp II and 5 paragraphs of text.

TAMPA MOTHER REPORTS SON, $2000 MISSING

The following day, the same paper repeated the story in a much abbreviated version - a mere 5 lines and no photo. This time the headline hinted at the doubts they fostered regarding Mrs. Tipp's assertion.

MOTHER SAYS CHILD MISSING

And if Lois Tipp wasn't going to alert the police, the newspapers would.

Two sheriff's department deputies visited Lois at the Woodside Screw Ball Inn, 2003 Tampa Bay Blvd, that same morning.

|

| The Tampa Times |

Lois told the police the same thing she had told the newspapers - she believed her son Bobby was snatched at the same time her $2,000 went missing.

The official police investigation obviously didn't include searching the property too extensively.

On the evening of September 26th, Woodside's customers were complaining about a nauseating odor of unknown origin.

Lois told them she had spread some rat poison around to deal with an infestation. Maybe they were smelling a dead rodent?

On the morning of the 27th, two of Lois' friends, Avie Thomas and Mae Everest, were at the tavern making coffee for themselves when a distraught Lois burst in and announced "He's dead in the refrigerator. Call the police."

.jpg) |

| Mae Everest |

Lois had found her son ... dead and stuffed into a large, unused refrigerator. The appliance was facing the wall and positioned behind the bar.

Mae Everest said that when came back from phoning the police, "the smell was terrible. Mrs. Tipp had the door partly opened to the refrigerator, and I could see part of a foot in a blanket. I began vomiting and ran out."

The police responded quickly and when they arrived, at 6:30 AM, the refrigerator door was ajar.

Bodily fluids were seeping out from the unplugged refrigerator. Lois Tipp was already mopping the tavern's floor.

Bobby's body, still stuffed into the refrigerator, was wrapped mummy-like in a sheet and blanket; two bullet holes in his head; a handkerchief was across the child's mouth. Bobby's knees were drawn up next to his stomach so that he would fit into the space. His only clothing was a pair of blue jeans.

.jpg) |

| The Tampa Times (Sept. 28, 1950) |

Lois now believed that whoever stole that $2,000 had killed her son. Bobby must have disturbed the burglar.

Police then found a blood-soaked mattress and sheet hidden behind a dresser in the tavern's storeroom. Lois Tipp had no immediate explanation for that.

.jpg) |

| The Tampa Times (Sept. 28, 1950) |

Lois was taken into custody as a person of interest. Accompanying Mrs. Tipp to the police station was her other son, 7-year-old Charley Joe.

If you haven't already figured out the direction this story is going - here's a line from the September 27th edition of the Tampa Times:

.jpg) |

| Tampa Times |

*The italics are my alteration to the newspaper's text.

While the deputies were questioning Lois, others were interviewing Charley Joe Tipp.

Charley said he woke up that morning to the sound of his mother crying.

"She said come here," Charley Joe said, "and I got up to see what it was all about. I saw my brother in the refrigerator. My mother kept crying."

"When will my mother be out?" Charley Joe asked.

Someone asked Charley Joe if he missed his brother. "He only died today," was the boy's answer.

The autopsy on Bobby revealed two bullets in the child's brain - one from a wound in the top of his head and another which was fired upward into his head from the area of his right shoulder. It was believed the bullets came from a .38 caliber weapon, but the police couldn't be 100% certain.

Police were able to establish that Lois Tipp had owned both a .38 caliber handgun and a .22 rifle. The pistol had been given to Robert Allen Tipp, Lois's estranged husband, several years earlier, as payment of someone's bar tab.

The rifle was found in a storeroom; the pistol had not been located. But just because Lois had a gun on the premises, it didn't necessarily follow that it was Lois who had fired it into Bobby's head ... twice.

Despite being questioned by detectives for 21 hours, Lois Tipp continually denied she was responsible for her oldest son's death but she did finally realize what the bloody mattress meant.

.jpg) |

| Tampa Times (Sept. 29, 1950) |

Lois asserted that she must have been the killer's target and Bobby was shot by mistake. In the darkness, the killer wouldn't have been able to see it wasn't her on the mattress.

Lois said the last time she had seen Bobby was the night before, when she had put him to bed in the roll-away cot she had set up for him in a bedroom in the back of the tavern.

Lois said she and Charley, who had undergone a tonsillectomy on September 22nd, slept apart from Bobby in the cottage. Charley had been at the Centro Asturiano Hospital on the 22nd and 23rd and only returned home on he 24th.

Their cottage and the tavern where located on the same property, connected by a breezeway.

When Lois awoke the next morning, Bobby was missing, as was the $2,000 in cash.

Lois went next door to tell Mrs. Avie Thomas that Bobby had been kidnapped and she paid the woman $3.00 to watch Charley while she went off to inform the newspapers.

Mrs. Thomas later told police that on Sunday, one day before Bobby was "kidnapped," she had heard Bobby screaming between 9 P.M. and 10 P.M.. Then everything became quiet.

.jpg) |

| Avie Thomas |

Curiously, this wasn't the first time neighbors had heard screams coming from the Tipp residence.

Six months earlier, on April 15, 1950, one of Mrs. Tipp's boarders, a Mr. Miller, was awakened by Bobby's screams. The time was 2 A.M. and the house Bobby was sleeping in was on fire. Mr. Miller quickly smashed through the door to Bobby's room and rescued the boy.

The night before that fire, Lois had put Bobby to sleep on a mattress in a house adjacent to the tavern while she and Charley Joe slept in one of the tavern's rooms. Earlier in the day, Lois had removed all of the furniture from the house.

Lois explained away the fortuitous furniture removal by saying that she had intended to renovate the house with an eye towards renting it.

The blaze destroyed most of the back of the house and Lois collected $3,100 from the insurance company. The $2,000 Lois said was missing was part of that settlement. Mrs. Avie Thomas was living rent-free in that partially burned building at the time Bobby Tipp's murder.

The police thought it suspicious that, only three weeks earlier, Lois had renewed the lapsed life insurance policies on both her sons and herself. The combined value of these three policies was $5,000.

.jpg) |

| Tampa Times (September 27, 1950) |

On September 28, 1950, Lois Tipp was arrested and charged with murdering her son Bobby. Police spotted what looked like blood splatter on black dress Lois was wearing and they submitted the clothing for analysis. Lois claimed the stains were red hair dye.

It didn't take long for the press to dub this case "The Icebox Murder."

*Quick note - this case is not to be confused with the unsolved 1965 "Ice Box Murders" of Fred and Edwina Rogers of Houston, Texas. The number one suspect in that double homicide has always been the couple's adult son, Charles Rogers. Charles Rogers disappeared on June 23, 1965 and was declared dead in 1975.

.jpg) |

| Frank Castrillon |

Frank F. Castrillon, a GI student at Jefferson High School, was not unknown to the police. He had been arrested ten times; his offenses included assault and battery, being an inmate of a gambling house, driving while drinking, a peace warrant and several charges of drunkenness.

Frank wouldn't be able to provide Lois with an alibi for Sunday night, which is when police suspected Bobby had been killed, but he had been with her the following evening.

Police also wanted to talk to another of Lois Tipp's boarders, Air Force Sgt. Henry Jacobs.

.jpg) |

| Sgt. Jacobs |

Charley Joe was taken to the Children's Home until his father, Robert Allen Tipp and Mr. Tipp's mother, Gladys Williamson, could fly down from South Bend, Indiana later that day to claim him.

Mrs. Williamson said, "I don't see how anyone could get mad enough at a little boy like that to kill him."

Robert Tipp said he felt maybe Lois didn't like Bobby "because he was named after me."

Lois had complained that Bobby was a problem child but his school teachers disagreed, as did Robert Tipp.

|

| The Tampa Times (Sept. 29, 1950) |

Robert had last seen his son Bobby three weeks earlier, "for only three hours."

That was when Lois traveled to South Bend, Indiana with Bobby to retrieve Charley Joe who had been vacationing with his father since Christmas of 1949.

Mrs. Williamson remembered how well the three hour visit had gone, "She was the sweetest I'd ever seen her be to Bob when she came up."

When Tampa deputies escorted Robert Tipp to the scene of the crime, Bobby's dog, Booter, was guarding the deserted tavern. Booter had been growling, barking and even nipping at strangers.

Robert hadn't seen the dog since March 1949, when he left Lois and the boys.

In July 1949, Robert moved back to Indiana. But Booter hadn't forgotten him and the dog bounded over as soon as Robert whistled for him.

When reporters asked Robert about his estranged wife, he said "I'm going to stick by her as long as possible. That is no more than right. I will stand by her until she is proved guilty."

The deputies described Lois as "hard as a rock and immovable."

Police gave Robert an opportunity to speak alone with Lois and afterwards he said "I think she is protecting someone. They say she's hard, but she wasn't hard with me. She puts on that hard front for the officers because she doesn't have any use for politicians - from a street sweeper to a governor. I think that might have been the reason she didn't report to officers in the first place that Bobby was missing. She doesn't have any use for them."

Members of the law enforcement community and various newspaper reporters swiftly initiated a deep-dive into the life of Lois Tipp. And as everyone would soon discover, Lois Tipp's life was one of lies, deception and now tragedy.

I'll start with some facts and then veer off into Lois's version of events.

Lois Margaret Tipp nee' Neely was born in Mississippi on July 2, 1902.

Her immediate family consisted of father Charles Jackson "C.J."

Neely, mother Drucille and older brother Pierre (born in 1897).

The town of Lois's birth was originally called "Washington" but it was renamed "Neely" after her father, C.J. Neely, became the area's first postmaster in 1907.

These postmaster appointments were easily decided - the Post Office was located in C.J. Neely's general store.

Subsequent Neely, Mississippi Postmasters were Pierre Neely (after C.J. retired from the position in 1940) and for a brief time, following Pierre's death, his widow Alpha Sutton Neely.

C.J. Neely was a wealthy man. Those riches came from his successful mercantile store plus 5000 acres of timberland, a sawmill, a turpentine business and some oil deposits.

Drucille Neely's brother, Dr. Joseph A. Leggett, DDS from Wiggins, Mississippi, would later tell a court that he had long suspected something was not right about his niece.

Dr. Leggett said he had come to this conclusion when Lois was 12-years-old.

Unfortunately, none of the newspaper articles recount any specific incidents that helped Dr. Leggett form this opinion.

Two psychiatrists who examined Lois Tipp, following her arrest, reported that they believed Lois had "been insane all her adult life" and that she had given "a very fantastic and inconsistent history of her life from about the age of 15."

This wasn't the first time Lois had sat down with a psychiatrist. She admitted to police that two years earlier she had gone to John Hopkins Hospital to consult a psychiatrist.

"I went there to find out if I was crazy because several of my neighbors had told me I was," Lois told Deputy Bob Spooner.

According to Lois, the doctors told her she "was run down."

A second uncle, Francis H. Leggett from Los Angeles, California, said the family always thought Lois was "mentally unbalanced." And the news of Lois having children came as a surprise to him and he suspects her parents would have been equally surprised.

At the time of her arrest, Lois's immediate family, the three people who would know the most about her past, were unavailable for comment because they were all dead.

Drucille Neely had died on February 1, 1944 (aged 67); C.J. Neely died on November 3, 1944 (aged 75); and Pierre died December 12, 1945 (aged 48).

Each obituary for the above three mentioned Lois as a surviving relative yet there was no mention of the Tipp children. Now, in fairness, not every death notice lists each family member but Drucille's obituary did include the name of Pierre's child, her granddaughter, Sandra Neely.

Surely, that obituary at least would have mentioned Bobby or Charley Joe Tipp, if the family knew of their existence. And what about Lois's youngest daughter Rhea?

Rhea Tipp was such a mystery that not even her own father, Robert Allen Tipp, ever met the girl. Now how is that possible?

When police finally spoke to Robert Allen Tipp, he had some pretty amazing things to tell them.

Robert A. Tipp had been married once before, from 1934 to 1941.

Robert and Maria Elizabeth Schwob's January 1, 1934 wedding ceremony was written about on the Society page of the South Bend Tribune on January 2, 1934.

They separated for years later, in March 1938.

In August 1938, Maria had filed for divorce, charging Henry with cruelty and asking for "limited divorce for three years."

On January 24, 1941, the two separated again and this time it was Robert asking for a divorce. Robert told the court that his wife Maria slept all day and kept him awake all night. He cited their frequent separations throughout the marriage. His request was granted three months later.

Following his April 1941 divorce, Robert had married Lois Neely.

Robert said he knew a little bit about his new wife's background.

He said Lois came from a prominent Mississippi family; she had been educated in an exclusive boarding school in Virginia.

Robert knew Lois had been married before, in New York when she was training to be a nurse, but her husband, Dr. William S. Bruckel, had died in a boating accident. The Bruckels had no children, as far as Robert knew.

Robert was aware that Lois had suffered a nervous breakdown following the 1937 death of her husband and it took her two years to recover.

In 1938, Lois had been an an inmate at a New Jersey psychiatric hospital.

Who knows who long Lois would have remained under a doctor's care or if it would have helped her had not C.J. Neely sent his son Pierre to New Jersey to have Lois discharged and brought home.

Robert said he and Lois had met in Gulfport, Mississippi while he was on vacation from his

job as a machinist as Bendix Aircraft Corp in South Bend, Indiana. Lois

was working as a nurse in a Gulfport, Mississipi hospital. They had met

through mutual friends. Six months later, they were married.

Robert said he and Lois had four children together during their 9 year marriage.

Robert Allen Tipp, Jr., whom they called "Bobby," was a twin when he was born on April 26, 1942; Bobby's sister, Barbara Jo Tipp, died following surgery for a bowel blockage, shortly after being born.

I did find a death notice for four-month-old Barbara Jo Tipp in the September 21, 1945 edition of the South Bend Tribune.

South Bend, Indiana being the home of Robert Tipp's mother and step-father.

GRANDDAUGHTER DIES

Mrs. Charles F. Williamson, 912

Lincoln Way West, has received

word of the sudden death of her

granddaughter, Barbara Jo Tipp,

four-month-old daughter of Mr.

and Mrs. R.A. Tipp, of Galveston,

Texas. Other than her parents the

child is survived by a twin brother,

Robert.

According to his birth certificate, Charley Joe was born on May 20, 1943 in New Augusta, MS - the same town as Bobby and Barbara Jo. His birth certificate bore the last name of Williamson, not Tipp.

Robert

A. Tipp's stepfather (since 1921 when Robert was 8-years-old) was

Charles Fletcher Williamson and Robert had been known to use both names

at various times.

The Tipp's youngest child, 4-year-old Rhea, whom Robert had never seen, was supposedly living with his wife's wealthy family in California.

Shortly before Rhea's birth, Lois had left town "on a business trip," and when she returned, it as without their newborn daughter. Robert said he spent 2 years trying to find the girl but Lois would never answer any questions asked of her.

Lois told police, "I'll go to the electric chair before I ever tell where she is."

Robert told police that he had left Lois in March 1949. "I stood it as long as I could," he said.

Robert would later describe Lois as "eccentric" and as someone who "didn't like no social life. I finally got tired of it."

In April 1949, Lois sued Robert for maintenance. Lois claimed Robert was lazy and had women companions.

Robert filed a counter suit, asking for a divorce and custody of the children. This move by Robert prompted Lois to amend her complaint; she was now asking for a divorce from Robert.

In July 1949, Robert moved back to South Bend, Indiana and resumed working for the Bendix Aircraft plant. He was employed as an X-Ray Technician.

Although Lois never revealed her daughter's exact whereabouts, she told the psychiatrist more about Rhea than she had told her husband.

According to Lois, Rhea was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi; she was now living with a woman named Linda who was "trouping on the road with a show."

Robert Tipp said that he was never present for any of the births. Lois always gave birth while he was away on a short-term work assignment or while Lois herself was out of town. And if he was being truthful, his wife never really showed any obvious signs of pregnancy.

Doctor Harold Nix examined Lois and he asserted that she had never given birth to any children.

The police now had to consider that Lois was guilty of not only murder but kidnapping.

Lois challenged the doctor's findings. In fact, Lois said she had given birth to not 4 children but 5.

During her sessions with the psychiatrists, Lois provided the following details regarding her years before Robert A. Tipp.

- Lois said that at age 15 she had married a man named Carroll, as a way "to get out of school," but the marriage had been annulled.

- Her next marriage was to Dr. William Samuel Bruckel. They had met in New York when he was an intern and she a student nurse. Sadly, the love story turned to tragedy when both her husband and their daughter Drusella drowned in a boating accident in the Long Island Sound. Lois herself narrowly escaped death that day.

As much as police and psychiatrists doubted everything Lois told them, they couldn't overlook the fact that much of the information came forth after Lois had received an injection of sodium amytole aka "truth serum."

Everything had to be investigated.

The first thing they realized Lois was lying about was her age. Lois was not 39 but 48. They also found proof that a year ago Lois had paid a Tampa plastic surgeon Dr. Anthony Perzia $600 for a facelift.

Police could only confirm one marriage for Lois and that was to Robert A. Tipp in 1941.

(I haven't been able to find the documentation to confirm this for myself, much to my frustration. The closest I came was an August 31, 1941 newspaper report of an Indiana marriage license being issued to Robert A. Tipp, 912 Lincoln Way West, Mishawaka and Mary Bair, 313 East Sample Street. That's certainly the address for Robert's apartment building but is Mary Bair Lois Neely? That was a legitimate street address, although the building is no longer there, and it would have been roughly 2 miles from 912 Lincoln Way West.)

Police could find no recorded boating accident in New York for a Dr. Bruckel. In fact, they couldn't locate anyone named William S. Bruckel. Nor could I.

However, Lois was speaking the truth when she said she had been a student nurse.

The 1940 US Census shows Lois Neely, already shaving ten years off her real age, was enrolled as a student nurse at Baltimore's John Hopkins University.

Of course, what Lois failed to disclose was to her husband Robert, her prospective employers, the police or her psychiatrists, etc. was after three months, Lois had been advised to leave because she "had no grasp of nursing."

The October 17, 1950 edition of the Tampa Times reported that Lois was a 1930 graduate of Woman's and Children's Hospital in New York City.

According to the January 24, 1951 edition of the Tampa Times, it's possible Lois had lived and worked in Cumberland, Maryland under the assumed name "Margaret LaRue."

"Margaret LaRue," police would soon discover, was one of many names Lois Tipp used over the years.

The Cumberland Hospital had employed a "Margaet LaRue" for a few months in 1930 before asking her to resign due to her "non-cooperation and impertinence."

I found a "Margaret LaRue" in the 1930 Census (enumerated on April 19th) living in NYC. That "Margaret LaRue" was one of nine roomers at 171 W. 81st Street in Manhattan and working as a practical nurse? The woman reported her place of birth as Mississippi.

I cannot find "Lois Neely" in the 1930 Census; she isn't in Mississippi living with the Neely family.

According to the 1940 census, Lois was living in Neely, Mississippi in 1935.

So, perhaps after things didn't work out in Cumberland, Lois made her way back to Neely, Mississippi for a little while?

Dr. Joseph A. Leggett, Lois Tipp's uncle on her mother's side, testified in court that when Lois introduced Robert to her family as her "husband," they didn't believe her.

According to Dr. Leggett, it didn't help that Lois at first said the marriage took place in New Orleans then, when no record of the union could be found there, she said the wedding had taken place "in New Haven, or somewhere else."

Robert says he and Lois had actually married in Dr. Leggett's hometown of Wiggins, Mississippi on September 5, 1941.

C.J. Neely died in November 1944, nine months after his wife's death.

His $500,000 estate was left to Pierre only. A

decision had been made to disinherit Lois because she, in their opinion,

was living in fantasy world and couldn't be trusted with any vast sums of money.

There was an "unwritten agreement" between C.J. Neely and Pierre that Pierre would provide Lois with occasional small allowances, on a "piecemeal basis."

Lois intended to challenge the conditions of her father's will but Pierre died in December 1945 before she had a chance to do so.

Pierre's will left everything to his wife Alpha and their daughter Sandra. And that included all of the money he had inherited from his father.

|

| Arlington Jones |

That same year, Lois and Robert purchased the Woodside Filling Station and Inn.

The Chancery Court had ruled against Lois and dismissed her claim on the Neely money. However, in August 1948, before the case could be tried in the Mississippi State Supreme Court, Pierre's widow agreed to an out-of-court settlement and Lois was awarded $12,000.

Naturally, Lois Tipp's work record was also riddled with contradictions and lies.

.jpg) |

| Lois Tipp, 1945 |

The woman's personnel record, Harris said, listed her a "single" and as her emergency contact, Lois wrote down the name "Mrs. R.A. Tipp."

On her 1946 application for employment at St. Joseph's Hospital, Lois claimed that she had received her nurses' training at Women's and Children's Hospital in New York City, and she gave Panami General Hospital and McCloskey shipyard (a wartime concrete shipyard in Tampa) as references. They rejected her application.

However, Lois did find work at the Southwest Florida Tuberculosis Sanatorium at Drew Field. She was a nursing supervisor there in 1947 and 1948; resigning, she said, because of ill health. The truth of the matter is Lois resigned when hospital officials demanded to see her nursing certificate.

Papers found at the tavern revealed Lois had used six different names throughout her adult life: Lois M. Neely, Lois M. Tipp, Constance LaFlue, Lois Margaret Bruckel, Loretta Schaffer and Margaret LaRue. These last two names were ones that Lois used during her stay in the NJ psychiatric hospital in 1938.The very last name, Margaret LaRue, is the one Lois is believe to have used in the early 1930's when working as a nurse.

Police also found some typeset pages of what appeared to be an unpublished novel, written by Lois.

It was on the pages of this novel that they finally found Dr. William Samuel Bruckel.

One paragraph described the death of Dr. Buckel and his son in a fishing accident. Dr. Buckel's widow is described as the beautiful, prominent sub-deb from New York. Her name - Lois Neely.

Police also found receipts totaling $2742.93 for various pieces of restaurant equipment purchased by Lois after the insurance payout (from the April 1950 fire) of $3141.49.

Her bank account showed a current balance of one dollar.

When arrested, Lois had $480 on her person, pinned to her clothing. Another $31 in cash was found at the tavern.

One of Lois Tipp's three attorneys, Mrs. Jane Brannon McMaster, petitioned the court to have all of the cash turned over to Robert A. Tipp as well as the keys to the Woodside Screw Ball Inn.

.jpg) |

| The Tampa Tribune (September 28, 1950) |

In additional to there being equipment worth "several thousands of dollars" at the Woodside Inn, there were already "morbid curiosity seekers chipping wood from the tavern."

McMaster also petitioned the court to allow Lois to attend Bobby's October 6th funeral.

|

| Irma Grese |

Sheriff Culbreath was reluctant to grant Lois Tipp's request to attend Bobby's funeral service.

In fact, Culbreath said he would permit it "only if a court order" required him to do so.

The State Attorney's office asked the sheriff to allow it and Culbreath acquiesced but not before telling the press, "There is no law that requires me or any other sheriff to do this. The woman has shown no remorse over the child's death and when the bloody mattress was placed in front of her she gave no indication of emotion. I believe the woman is guilty of the brutal and grisly slaying of her son."

|

| Tampa Tribune (Oct 7, 1950) |

Charley Joe did not attend his brother's funeral. He remained at the Children's Home, where he had been since Lois was arrested.

Reporters strained to hear the hushed conversation between Lois and her mother-in-law, Gladys Williamson.