Clara Branch had money and her friend Marie Jarvis Berlin wanted some of it. It was as simple as that.

Marie Berlin

Clara's brutal murder on November 14, 1919 (a Friday) wasn't one of cold calculation but one of impulse, motivated by greed.

By all accounts the two women were friends, had been for years.

And yet, Marie (aged 31) knowingly and willingly struck her friend multiple times in the head and face with a hammer - thus prematurely ending the life of 41-year-old Clara Branch. How does that happen?

I've tried to find the origins of the friendship between Clara and Marie but, despite my best efforts, I can only speculate and, as regular readers of this blog will already know, I don't engage in large scale guess work. However, later in the narrative, I'll reveal the slender threads that may tie the two women together.

.jpg) |

| Brooklyn Eagle (Nov 16, 1919) |

Two quick notes before we begin:

1 - The weapon used to kill Clara Branch is described in various newspapers as either "a hammer" or "a hatchet." I'm thinking it might have been a multi-use tool such as this one:

2 - Marie Berlin used several names throughout her life. Berlin is her maiden name. Her husband's legal name was Leo Strauss but he used the stage name Fred Warren. After her 1910 marriage to Leo, Marie Berlin was known to go by her maiden name or Marie Warren or Marie Strauss. In the interest of consistency, I'll stick the name she was born with. In various newspaper articles that I'll be quoting from, she'll be referred to as Marie Warren or "the Warren woman." Don't let this throw you. She was also said to use the alias Marie Burlingame but, if she did, it wasn't with any regularity.

Roughly two weeks before her death, Clara Branch had opened the Valley Stream, NY home she shared with Captain Henry Wright (approx. 56 yrs) to the down-on-her-luck Marie Berlin.

Marie's divorce from notable black-face performer Leo Strauss eight years earlier was a likely reason.

Leo as "Fred Warren," was one half of "Warren and Blanchard."

I don't know how Leo Strauss and Marie Berlin met or how long their courtship lasted before they tied the knot but Warren and Blanchard often performed at The Grand while in Indianapolis.

Indianapolis Star (Jan 23, 1910)

Marie Berlin and Leo Strauss married on Feb 12, 1910 at the Nic. Bosler Hotel, located on the southeast corner of Second Street and Jefferson Street in Louisville, Kentucky.

University of Louisville Photographic archives

|

| a 1901 ad for the Nic. Bosler Hotel |

Witnesses to the event were Mr and Mrs. Nic Bosler, the hotel's proprietor, and Helen Berlin, Marie's older and only surviving sister.

Marie was the youngest of James and Frances Berlin's three children. Sadly, their eldest daughter, Esta Otto Berlin, died on May 6, 1907 from a complication of inflammatory rheumatism and pleurisy, which had affected her heart. Esta was 25 years old when she died.

Also present for the wedding was Leo's long-time partner Al Blanchard.

Warren & Blanchard were in town performing for four days at The Mary Anderson Theatre. The wedding ceremony was scheduled for 10 AM, before the matinee performance.

.jpg) |

It's possible Marie's career in vaudeville was short-lived and began only after marrying into it.

This was Marie's first marriage; Leo's second.

Leo's first wife was actress Alice K. Mack.

According to court records, Leo and

Alice had married in Hoboken, NJ on May 20, 1888; in the fall of 1903,

Leo moved out of the marital home, never to return.

Leo and Alice each filed for divorce in 1905, at different times and in different states. Leo filed first in Illinois, claiming Alice abandoned him.

Alice filed afterwards in New York. Alice asserted the Illinois divorce decree meant nothing to a New York resident.

Alice K. Strauss accused Leo of adultery, desertion and non-support.

Marie Berlin was not identified by Alice K. Strauss as the woman with whom Leo Strauss was living in a state of open infidelity with after he deserted her. That distinction belonged to Alice Marshall, aka Alice St. Clair.

Alice claimed her own physical ailments made it impossible for her to work and she was reliant on her husband's income. Their divorce was a prolonged and litigious one.

Leo was arrested on October 22, 1907, while waiting in the wings of Manhattan's Keith & Proctor Theatre on 58th Street. Warren & Blanchard hadn't performed in New York for over two years. Adhering to the adage that "the show must go on," the deputy sheriff allowed Warren & Blanchard to perform that evening before taking Leo into custody.

Ultimately an appellate division of the Supreme Court ruled in Leo's favor - his Illinois divorce was valid. Alice Strauss's earlier acceptance of a lump sum payout of $1,000 (rather than weekly alimony payments of $15) indicated her acknowledgement of the Illinois divorce decree. Leo's arrest order was vacated.

Leo's 1910 marriage to Marie Berlin ended before their first anniversary. In January 1911, Marie and Leo were divorced. When Variety magazine announced the divorce, the article stated "His wife was not a professional."

Marie, when Clara took her in, was unemployed and apparently hiding from the New York City police.

She had been charged with stealing a $50 stick pin from an unnamed gentleman. (The Brooklyn Eagle reported on November 17th that Marie had obtained a piece of jewelry belonging to a Manhattan man through coercion. Marie later said she's pawned a diamond ring.)

Good news though - a reversal of fortune was just around the corner for Marie Berlin as she had recently applied for a job as an investigator with the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Marie told people she was simply waiting for them to check her references.

Marie would later claim to have been an operative with the Baum Detective Agency at 174 Fulton Street in Manhattan.

Henry Wright, it was said, wasn't very fond of Marie but he tolerated her presence. There was some general confusion in the newspapers over who actually owned the house in which Clara was killed.

On November 16, 1919, two days after Clara was killed, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle identified her as the homeowner and listed Henry and Marie as "roomers." One day earlier, a reporter for the same newspaper assigned ownership of the house to Captain Wright.

The New York Herald reported (Nov 16th) that Henry Wright, a noted commercial fisherman, "employed Mrs. Branch as a housekeeper in the house he maintained of Hendrickson Ave, Valley Stream."

Newspaper accounts routinely described Clara Branch as Henry Wright's "housekeeper" but I suspect their relationship was not simply one of "employer and employee" or "landlord and tenant." Clara and Henry slept in separate bedrooms but it seems there was a genuine affection between the two.

Henry was married but had been living apart from his wife Adelia for the last three years. The two had married in 1885 and, while the union produced no children of their own, Henry and Adelia were parents to an adopted child - Cora May.

Cora was 29-years-old in 1919, married to Percy R. Smith and the mother of two daughters. Adelia was living in East Rockaway and worked outside the home as a domestic.

.jpg) |

| Captain Henry Wright and Clara Branch - NY Daily News (Nov 17, 1919) |

Clara Branch was said to be married but no newspaper seemed to know his name. According to the New York Tribune, "The Branch woman's husband, it was said, is alive, but his whereabouts are unknown."

Clara handled the household finances and Henry routinely handed a portion of his wages over to Clara for depositing in the bank.

The New York Herald described Captain Wright as being "a big man, of a type common among the Long Island villages where many of the residents get their living from the sea. His face has been tanned by weather and he had a heavy mustache, which, like his hair, runs to gray."

Who actually owned the house in which the murder occurred was the least sensational aspect of the crime. This murder had been brutal and the suspected female killer had ties (however tenuous) to show business.

The murder house, now long-gone, was described (by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle) as being "in a woodland section of Valley Stream known as Tiger Town, close to the Lynbrook boundary line."

New York's Daily News also places the house on Hendrickson Ave.

Boundary lines have shifted since 1919, thus making it difficult to pinpoint the exact location of the house.

Here is a very dark picture of the house -

.jpg) |

| NY Daily News (Nov 17, 1919) |

The night before Marie Berlin beat her friend to death, the three of them (Clara, Marie and Henry) had stayed up late playing penny ante poker in Clara's bedroom. Marie chain-smoked factory-made cigarettes while Clara rolled her own from a package of tobacco.

As he was turning in for the night, Henry heard Marie ask Clara for a loan of $50 and he had heard Clara refuse. Clara was extremely hard of hearing so no doubt the voices were raised just to be heard. There's no real indication that the two women argued over the money.

On the morning of November 14th, Henry left the house at 7 AM to put in a full day's work on his charter fishing boat, The Commodore, which was docked at Wreck Lead.

|

| 1916 photo of The Commodore - could that be Capt. Wright? |

Henry told reporters:

"It is a terrible thing to think that when I left Clara Friday morning she smiled as I kissed her, and she was still smiling when I waved my hand to her from the street. But then to come home to that terrible mess. Oh, it's awful. It's terrible."

We only have Marie's word for what transpired between the two women after Henry's departure.

When Henry returned at 6 PM that evening, the house was in complete darkness and the door unlocked. Marie Berlin was gone and Clara was dead in her upstairs bedroom; her head bashed in, blood everywhere.

Henry telephoned Dr. J.M. Foster, a local physician, from his neighbor John Loeffler's house.

Dr. Foster notified the police, specifically Constable Fred Miller of Lynbrook.

Constable Miller brought the county's coroner, Edward T. Neu, along with him to the scene of the crime.

Detectives Carman Plant and Thomas V. Barbuti took over the investigation; assisted by Constables Fred Miller, Leonard Thorne and Charles Anderson.

The following description of the crime scene comes from the Brooklyn Times Union newspaper's November 15th edition:

"The body was lying curled up in bed, with the head in the middle of the bed and the right foot extending over the edge. The body was clothed in a nightgown and a short petticoat. There were three terrible gashes in the head. Two were in the back and were each about five inches long. Third gash was along the nose on the right side and extended into the brain. The right eye was knocked out by this blow.

"There was a cut on the right hand and another on the left arm, evidently made by the hatchet when the woman put up her arms to ward off the blows. It is believed probable that the woman may have been attacked while in bed in the morning.

"A bloody hatchet lay at the foot of the bed. And the shape of the cuts on the head and the nose showed that they had been made by this hatchet."

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle provided quotes from Dr. A.D. Jacque and Dr. F. S. Sherman:

"Mrs. Branch had met her death from a compound, bursting fracture of the skull."

"..the blow on the right side of Mrs. Branch's head had been struck after she was dead. Every bone in her skull except the lower jawbone had been crushed by the murder or murderess."

It was initially believed the killer was a man because of the obvious force of the blows. Blood splatter on the walls went as high as the ceiling. A blood-soaked towel was laying on a chair. A second bloody towel was found in a closet.

In one of Clara's hands was a whisp of dark hair, believed to most likely removed from the assailant's head during the struggle. Dr. Otto Schultze was tasked with making an analysis of the hair.

Judging from Clara's physical description, she would have been capable of fighting back, given sufficient warning. Clara was five feet eleven inches tall and weighed 180 pounds.

The Evening World newspaper reported on November 15, 1919:

"One of her stockings was on and one partly on, which led the authorities to believe the woman was struck down while she was getting up."

Fingerprint expert Charles W. Hansen was brought in to examine the multitude of bloody fingerprints found throughout Clara's bedroom.

The murder weapon, a combination hatchet and hammer with a 10 inch handle, was left behind at the scene; it was wiped clean of fingerprints and blood. The ax end of the weapon showed signs of being broken before it's employment in the murder.

Robbery was a believed to be a possible motive but there was much of value left behind - a diamond ring, a gold signet ring bearing the initials "C.D." and $51 in cash were found in a small bag pinned to the band of the woman's skirt.

A 32-calibre revolver was found under the pillow. There was no indication Clara had made any attempt to defend herself with the weapon. The gun belonged to Capt. Wright.

Detective Branch told a NY Times reporter, "Wright told us he had had his revolver about the house for some time but that it had not been used in years."

According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

"The revolver was of an old-fashioned type and apparently had not been fired for some time, though there were cartridges in every chamber, two of them having been discharged. The weapon was hardly in a serviceable condition except as a means of frightening intruders."

A further examination of the house provided additional clues.

Bloody fingerprints, small enough to be that of a woman, were found on the dresser in Marie Berlin's bedroom. Also in Marie's room was a traveling bag which police surmised had been packed in a hurry then left behind. A bloody cloth was located under Marie Warren's bed.

According to the New York Tribune, "a bottle of heroin was found in the cottage." The New York Times reported the bottle had been found in Mrs. Branch's room.

This gave rise to the theory that Clara may have been drugged before the attack. Arrangements were made for Clara's stomach contents to be examined by Dr. Herbert Pease, formerly of the State Department of Health laboratory.

Henry Wright was an obvious suspect but his alibi was quickly substantiated by several people who saw him coming and going from the home on the day of the murder, as well as John F. Lawson, The Commodore's ship's mate.

Henry Wright revealed to police that Clara should have had much more than $51 on her; he had given Clara $251 Thursday night, to be deposited in a bank account. Robbery was once again the main motive.

Police found bloodstained money in Wright's possession when he was taken into custody. Henry said the bills had been given to him by his mate, who cleans fish and often has bloody hands.

While there were some minor discrepensies regarding Henry's movements at specific hours of the day overall, he was in the clear. The Evening World newspaper reported "The Coroner's physician said she had been dead at least six hours" at time her body was found.

All the same, Henry Wright was held as a material witness with bail set at $5,000.

A New York Times reporter spoke with Adelia Wright, Henry's estranged wife, at her home in East Rockaway and told readers: "she was confident her husband was not implicated in any way in the murder. She admitted that she and her husband agreed to separate three years ago because of Mrs. Branch, whom she said she had never seen, to her knowledge."

The detectives also wanted to talk to Marie Berlin, who was nowhere to be found. Newspapers reported this fact and provided every name Marie was known to use: Marie Berlin, Marie Warren and even Marie Burlingame. She was described as being "five foot six inches tall, weighs about 150 pounds, has fair complexion, regular features and dark hair. She wore a dark cloth suit."

Late in the afternoon on November 15th (the day after the murder), to the astonishment of all, Marie Berlin walked into the district attorney's office in Mineola.

Marie said she'd read about the murder in the newspaper and wanted to help in any way she could.

According to Marie, when she left the Wright/Branch home at 9:30 AM, Clara was still alive. Her day after that was jam-packed with travel to Manhattan and time spent in the company of friends. She readily provided every detail.

Marie Berlin said she walked from the house on Hendrickson to the trolley line via Merrick Road; she boarded a trolley at Hempstead Crossing, and rode to the city Line. Once there Marie boarded an elevated train for Park Row. She went into Perry's drug store and phoned her chief alibi witness - actress Catherine Hayes, who was staying with their mutual friends Mr. and Mrs. Aaron Hoffman at 414 Riverside Drive in Manhattan. Marie went to Riverside Drive and stayed at the Hoffman's until 9:45 PM.

(Aaron Hoffman was an American playwright and lyricist who worked closely with many vaudevillians. His wife's name was Minnia Z. Hoffman.)

Marie, Catherine and Mrs. Hoffman then drove by car to The Republic Theatre (209 W. 42nd Street), where they were joined by Mr. Hoffman. They watched a portion of the evening's performance and had dinner at a restaurant afterwards before going back to Riverside Drive, where she spent the night.

(I've done some research and the play in question would have been "A Voice in the Dark." This, ironically, was a popular melodramatic murder mystery written by Ralph E. Dyar in which two woman are the chief suspects in a murder. It had opened on July 28, 1919 and relocated to the Shubert Theatre on December 29, 1919. A silent film adaptation was produced in 1921.)

NY Times ad for the play (July 28, 1919) _-_2.jpg)

1921 ad for the film adaptation

While police worked to verify Marie Berlin's alibi, she too was held as a material witness and bail was set at $5,000.

Both Henry Wright and Marie Berlin were driven to the murder house and one-by-one taken to the scene of the crime. Detectives were checking their reactions to the horror before them.

Marie supposedly said, "How awful! Who could have done this? I'm sure I don't know."

"Please don't accuse me of this awful thing," The New York Times reported Marie Berlin had pleaded. "Clara was like a mother to me. She gave me money whenever I needed it and was good to me in many other ways. If she could only talk she would tell you I did not kill her."

Detective Carman Plant asked Marie about the $50 she'd asked to borrow from Clara.

Marie denied quarreling with her friend over the refusal on Clara's part.

At first Marie said she'd wanted to money to finance a trip home to see her family. Then Marie changed her story and admitted she needed that money to redeem a diamond ring she had in pawn. (Could this be the jewelry Marie was accused of stealing?)

A physical examination of Marie Berlin by Mrs. Phineas Seaman, matron at the Nassau County jail, revealed fresh scratches on Marie's left shoulder, on both wrists and on her arms. .jpg)

Det. Plant & Bess

Marie explained these scratches were obtained when she was playing with Clara's pet, a brindle bulldog named Bess.

Marie asked for a cigarette and Detective Plant said he had didn't have one to give. He then casually asked Marie what her preferred brand of cigarette was. Marie named a popular Turkish variety.

From that moment until she confessed to the murder, Plant arranged it so that every man who passed by the cell in which Marie was being held, he would be smoking her brand of cigarette. Whenever Marie asked if they had a spare cigarette for her, she was told they had just smoked their last one.

Plant promised Marie she'd be given a cigarette after she told "all she knew" about the murder.

Charles W. Hansen, who was taking fingerprint impressions from anyone involved in the case, obtained Marie's impressions. These would later be a match for the bloody fingerprint found on the side of drawer of a dressing table in Marie's bedroom.

The detectives employed a time-honored investigative technique during their four hour interrogation of Marie Berlin - they lied about the evidence against her. Marie was told her fingerprints had also been found on the handle of the hammer that was used to kill Clara Branch.

It was reported that Marie sat silently for five minutes, her face in her hands before saying, "Yes, I did it. I want to confess everything."

Marie Berlin was taken from the jail to the district attorney's office. Marie's first request upon arrival was for a cigarette.

The District Attorney handed her a whole pack then he heard Marie's confession.

Weeks released the confession to reporters on November 17, 1919:

"I alone killed Mrs. Branch; no one else is implicated.

"I had an argument with Clara Branch on Friday morning. I went to her room and asked how she felt. She replied 'Not so well.' Clara then asked me to get some medicine for her. I noticed that when she was getting the money for the medicine that she took a roll of bills from a pocket in her petticoat. I was broke. I needed money and had asked her for some the night before, but I was refused. I again tried to persuade her to lend me some.

"A quarrel followed. She called me a crook. I resented this. She struck me in the face and said, 'You leave this house and leave it now or I will shoot you.' I knew that there was a gun in the house. I knew Clara Branch well. I knew that when she said 'I will shoot you,' she meant it. I felt the sting of the blow she delivered. I left the room and went downstairs to the dining room on the lower floor and got a hatchet which I knew was there, having used it myself on several occasions.

"I then went upstairs stealthily. I saw Clara sitting on the bed with her back towards me. I stole on her and hit her on the head with the sharp end of the broken ax. I saw her fall backwards.

"I do not remember how many blows I delivered. I saw the blood splatter all over. It was on my hands. I seized a towel from the floor, wiped my hands and threw the towel in a closet. I then took the roll of money from the petticoat pocket and left the house. There was $135 in the roll.

"I went directly to the home of Miss Catherine Hayes, who lived with a Hoffman family on Riverside Drive. I am sorry I killed her and I am ready to meet the penalty."

Reporters asked Weeks if Marie Warren broke down while making the confession or simply wept.

"I wouldn't call it weeping," D.A. Weeks said, "but at times she showed signs of emotion. After the confession, she said 'I am sorry I did it, But I am ready to pay the penalty no matter what it is.'"

Weeks, in his statement to the press had omitted the fact that, on the day of the murder, Marie had paid $25 to the Reisenweber Hotel's attorney Jerome Wilzner, for access to her trunk of personal belongings which had been in storage at the hotel.

The Reisenbewer Hotel was located at Eighth Ave and 58th Street, near Columbus Circle.

|

| a 1905 photo showing Reisenbewer's Hotel, on right (NYPL collection) |

Marie had recently received notification that if she hadn't made good on her unpaid hotel bill, her trunk would be sold on November 14th - the day of the murder.

What was in the trunk?

Marie claimed she gained access to the trunk for the express purpose of retrieving theatrical contracts belonging to her friend, actress Catherine Hayes.

(Quick note - there were several celebrities named Catherine Hayes but we can easily rule out two of them.

The most notable was an internationally popular Irish soprano known as "The Swan of Erin." This cannot be the woman Marie Berlin had an association with as this Catherine Hayes died in 1861.

It's also worth mentioning that the mother of legendary actress Helen Hayes was named Catherine Hayes Brown and that Catherine, who was known as "Brownie" to her friends, had achieved some degree of celebrity status during her life as a result of her daughter's career and the 1940 non-fiction book she penned, "Letters to Mary." Brownie died on July 1, 1953, at the age of 76 yrs. She was not an actress herself so 'Brownie' is not the former friend of Marie Berlin.)

I think it's likely that Marie's actress friend is the same Catherine Hayes who performed on the vaudeville stage with her sister Sabel Johnson.

|

| Los Angeles Herald (June 23, 1907) |

The detectives working for the District Attorney's office had a look inside the trunk for themselves and proceeded to investigate some of Marie's correspondents.

One letter they'd found in the trunk was sent to Marie Berlin from a "May Smith."

The contents of the letter was made public and The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reprinted it in their November 18, 1919 edition:

Dolly Dear,

Your letter received Saturday. I was glad to hear from you, as it seems so long since I heard from you. Well, I am still at M. Could not get anything downtown, but if I make a move will let you know. Things are about as usual. The chief was asking for you. B has been on good behavior as there is nothing to drink. Will get me a dress next week, maybe. Haven't you found anything yet? Why don't you phone someone, the doctor or somebody? Did you call Russell again? Why don't you take a run down to Far Rockaway and see if you can't find George Van? I am going over to mama's today so you can see I have a fine time in view. I do so get the blues, but I guess it is coming to me so I guess I will have to make the best of it. You had better stay down there until something turns up for you. Be careful how you write. That letter was fine as M. is doing some talking, but no one minds her. What do you think of Sadie? Just wait until I see her. We will have to arrange it so I can meet you in New York.

I can let you know and I can meet you in the Hudson Tubes, so write me. Your letters always come in the mornings, but I can't let you know as I never know when M. is going to stay home. Twice last week he was home in the mornings at 10:30 and once at 12.

Give my love to Clara and tell her not to drink too much. Regards to the Captain. Write me so I will know what to do. Be good and don't worry.

Lovingly, May.

Following her confession, Marie Berlin was committed to the Nassau County jail.

She was charged with murder and held without bail. At her arraignment, Marie told the Judge, "I am guilty."

Having been told that she couldn't enter such a plea in a capital case, Marie replied "I'll plead not guilty if you say so but I am guilty and want to have it over with as soon as possible."

It was reported that Marie wept continually and smoked cigarettes incessantly to sooth her nerves.

Captain Henry Wright was no longer a suspect and he was released.

A second letter from May Smith to Marie, sent special delivery from Belleville, N.J., was intercepted by police.

"Don't be afraid; that fellow isn't going to talk and everything will come out all right."

Marie refused to explain the contents of either letter.

Is it just me or does it sounds like May Smith is asking Marie if she had any success in procuring drugs?

On November 18, 1919, the Boston Globe reported:

"In the jail in Mineola last night Mrs. Warren appeared to be on the verge of collapse. Mrs. Seaman, the matron summoned Dr. Guy F. Cleghorn. After the physician left, Mrs. Warren sat on the edge of her bed smoking one cigarette after another. To a fellow prisoner she confided that she had used morphine some years ago, but had recently broken herself of the habit and substituted cigarettes for the drug." You'll want to remember this declaration on Marie's part.

(It is possible the fellow prisoner referred to in this article is Sarah Files from Glen Cove, NY. Sarah was in the cell next to Marie and awaiting trial on a charge of having drowned her infant child.)

Despite Marie's confession, the investigation continued.

Police learned that May Smith had been employed as a housekeeper for the last nine months in the Belleville, NJ home of Mrs. Sarah Halsey. Sarah Halsey was a 38-year-old widow, whose occupation one year later (in the 1920 Census) is listed as "operator of a pen factory."

That same 1920 census lists "May E. Smith" living as 37-years-old, single and living as a boarder within the Halsey house, her occupation is "manicurist in a barber shop."

May Smith traveled from New Jersey to Mineola on November 20, 1919 to speak with the District Attorney.

The Brooklyn Eagle reported that "Mrs. May Smith, Mrs Warren's friend, is expected to make important disclosures in the relations of the clique of which Mrs. Warren and her victim were alleged members."

Oh, how I wish these disclosures were made public. Unfortunately, I haven't found any accounting of her statements to investigators, only that neighbors of Mrs. Halsey stated Marie had visited her friend twice in the summer.

And the detectives still wanted to hear from Catherine Hayes.

A trip to Manhattan to speak with Miss Hayes and the Hoffmans proved fruitless. Detective De Martini was unable to locate them.

Fortunately, Catherine was anxious to make contact with the police regarding this matter and anxious to rid herself of vital evidence.

Catherine Hayes telephoned the Nassau County detectives from Manhattan and said she wished to turn over the pocketbook and she'd hoped distance herself from the investigation. She reportedly told Detective DiMartini, "Here take it. I don't want any thing in my hands that belonged to that murdered woman."

Miss Hayes surrenders the bag (Phil Litchfield drawing)

Miss Hayes's official statement on the matter would be provided to the District Attorney during a two hour interview in his Mineola office on November 22, 1919, after Marie had confessed to the crime and implicated nobody but herself.

Catherine Hayes said Marie arrived at her Manhattan apartment on the day of the murder around 1 PM. Marie handed her an old, weather-beaten pocketbook and said "Here, take care of this for me." When Catherine opened the pocketbook she found $131.00 in it. In today's money $131.00 = $2,310.

Whether or not Marie went to the theatre and a restaurant the day of the murder wasn't addressed in any of the later newspaper accounts.

Also, two red herrings which had been widely reported on early in the investigation - that of John Loeffler seeing Marie Berlin in Valley Stream at 3:30 PM the day of the murder and two hunters who'd been spotted knocking on the front door of the murder house - each faded away completely. With Marie's confession matching the physical evidence, all other avenues of inqury were dropped.

In accordance with a wish expressed often before her death, Clara was cremated.

Her body was delivered the Fresh Pond Crematory in Middle Village, NY. The burning took place on November 18, 1919, at 3:45 PM.

There were no mourners present and there's no indication that anyone claimed her ashes.

The thing Marie Berlin was said to have dreaded the most in the aftermath of her confession was her mother's reaction to news that her daughter had killed someone.

"No word of this must get to my mother," Marie supposedly told the District Attorney. "I may be guilty, but she must not hear of it."

Marie needn't have worried; Frances Cordelia Berlin stood by her daughter.

A telegram from Frances arrived on November 19th - "I hear you are in trouble. Do you need help?"

Marie's reply was just as brief and to the point - "I am in trouble. Somebody better come."

Marie, it was reported, "had been led to confess in the hope that clemency might be extended her if she saved the State the expense of a prosecution."

As the days progressed, Marie started to regain some of her stamina and she began focusing on her defense.

The following is what the Brooklyn Times Union newspaper reported, on December 19, 1919, regarding Marie's arraignment:

"The young woman was clad in a black suit and wore a dark sailor hat and a white collar. She did not seem the least bit perturbed over the ordeal, but, on the contrary, seemed particularly interested in her surroundings. Immediately preceding her appearance in court she was taken into the clerk's room, where she signed the order which signified her lack of funds to employ counsel, and chatted and laughed with County Detective Carman Plant, the man who wrung the confession from her."

Marie Berlin, having no money to hire an attorney, was appointed counsel by Supreme Court Justice Kapper. Representing the accused was Charles Newbold Wysong. Wysong had already been acting as Marie's counsel since her confession but now it was official.

|

| circa 1910 |

Wysong's client was Julia's husband, 67-year-old Dr. Walter Keene Wilkins.

Dr. Wilkins was ultimately found guilty of bludgeoning his wife to death. Wilkins later hanged himself in his jail cell.

An article in the Brooklyn Times, appearing one month prior to Wysong's appointment as Marie's lawyer, stated the following:

"Mrs. Warren is preparing, apparently, for a defense of insanity. She told her attorney, Charles N. Wysong, today that she had not felt right since an attack of influenza in the spring. She has a violent temper, she said. Once she had a quarrel with a relative and afterward other relatives talked of putting her in an insane asylum."

Mr. Wysong told reporters that same day that his client was morose and melancholic:

"There is no doubt in my mind, after my conference with Mrs. Warren (Marie Berlin), that she comes from a family that has a strain of insanity. Her father, James Berlin of Indianapolis, died in an insane asylum when she was 14 years old. Her uncle, George Jarvis of Pasadena, CA died in a hospital for the insane two years later."

Mr. Wysong wasn't wrong in his claims of insanity within Marie's lineage.

Her father James Tripp Berlin died at the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane on November 29, 1902. Cause of death for the 41-year-old carpenter was "Paresis." According to the death certificate, James T. Berlin had been a patient at that facility for "1278 days" or 3 and a half years.

Google tells me: "Paresis" is "an inflammation of the brain in the later stages of syphilis, causing progressive dementia and paralysis."

|

| Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane (1903 photo) |

George A. Jarvis, Marie's maternal uncle is listed on the 1900 census as a boarder with the Berlin family. At the time he was employed as a bartender.

The New York Herald claims George A. Javis died in a Pasadena, CA insane asylum five years before Wysong's client killed Clara Branch. So, George died either in 1904 (two years after his brother-in-law James Berlin died) or in 1914 (five years before Clara's death).

My research leads me to think George Jarvis died in 1914, even though I cannot find a death record for the man. I say that because I believe I've found a divorce decree being granted to his wife of three years, Grace O. Jarvis, in June 1914.

While I'm not able to confirm the nature of George Jarvis's death, as outlined by Charles Wysong, if it's true, there was evidence of insanity of both sides of Marie Berlin's family.

Charles N. Wysong told reporters that Marie had made the following statement to him: "Sometimes I think I am crazy for I don't know what I'm doing. I must have been crazy, otherwise I would not have done this."

Wysong engaged Dr. Minas Gregory, an alienist from Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, to examine his client.

I don't know what Dr. Gregory might have determined regarding Marie Berlin's diminished capacity; the case never went to trial so Dr. Gregory was never called to testify and his findings were not made public.

After negotiating with the District Attorney, Marie Berlin decided to plead guilty to murder in the second degree. It was a compromise, to be sure. Marie's attorney sought a manslaughter conviction and the State, having charged Marie with murder in the first degree, refused to accept a manslaughter plea.

On January 12, 1920, Justice Stephen Callaghan imposed upon Marie Berlin a sentence of twenty years to life in New York's Auburn Prison.

.jpg)

Auburn Prison (1905 photo, from the Cayuga Museum)

Clerk of the Court Daniel Sealey recorded Marie's personal information. She said she was an investigator by profession, her last known address was 161 W. 79th St., Manhattan and her marital status was that of widow.

I don't know if "widow" is accurate. Yes, Leo Strauss was dead; he had died at 56 years old, from heart disease on January 2, 1917 at his home in Elmhurst, NY but he was married to another woman at the time, one Wally Warren.

Leo Strauss (aged 51) had married German-born Elsbeth Alma Wally Geyer (aged 24) in France on April 11, 1911 (three months after his divorce from Marie). Leo and Wally's son, Frederick, was 5 years old when Leo died.

In 1920, as Marie was being hauled off to prison, Wally Strauss was employed as an actress at NYC's Hippodrome.

Marie Berlin was checked into New York's Auburn State Prison on January 21, 1920 under her legal name Marie Strauss. She eventually earned the trust of the prison staff and she was soon working as a clerk in the warden's office.

Flash forward nine and 1/2 years -

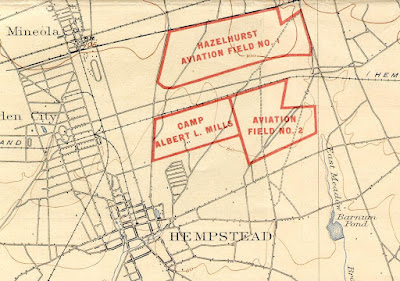

There was a riot at the Auburn Men's Prison on July 28, 1929 involving 1,700 inmates. Four prisoners escaped, two inmates were killed, five guards were wounded and six buildings were destroyed by fire. The damage was assessed at $450,000.

|

| Press and Sun Bulletin (July 30, 1929) |

Shortly afterwards, Marie heard rumors about the female inmates planning to stage a similar revolt by setting their prison ablaze. Marie warned her boss, the warden, of those plans and it seems the insurrection was dealt with.

To show his appreciation, Auburn's warden later submitted a formal recommendation to the governor, asking for clemency for Marie.

On December 11, 1929, Auburn's Warden and six guards were taken hostage by a group of inmates, some of whom had obtained guns in the July riot and concealed them in the interim. This uprising caused the death of Principal Keeper George A. Durnford as well as eight prisoners. Three inmates were later charged, convicted, and executed at Sing Sing for their roles in the riots.

On November 17, 1930, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt granted Marie's commutation.

The International News Service informed their readers on November 18, 1930 that:

"The governor said that the state parole board after a careful examination of the case 'has unanimously recommended clemency.' The governor also revealed that the acting warden of Auburn has urged commutation of the sentence.

"'He states,' the governor wrote in a memorandum, 'that for several years her services in the prison office have been invaluable. Following the riot at Auburn prison in July 1929, she warned him of the plan of some of the inmates to set fire to inflammable material stored in the women's prison and in so prevented what might have been a catastrophe.'

Image from the Fay Family album website

"The governor said that the woman's mother lives in Indiana and 'is very old and in serious physical condition and needs her daughter.'"

The US Census, recorded on April

15th of 1930, shows Marie's 71-year-old mother Frances Cordelia Berlin

living Indianapolis, Indiana with her 62-year-old sister Mary B. Jarvis.

Mary was still working, as a clerk at an insurance company.

Of Frances Berlin's three children, only Marie was still alive.

Frances's

other daughter, Helen Ayers nee' Berlin, had died on August 9, 1928 at

the age of 43. Cause of death for Helen was "Tuberculosis of Pleura and

Peritoneum."

As reported in The Owensboro Messenger on November 19, 1930:

"The formal recommendation for clemency came from the newly created parole board, which told the governor that although she pleaded guilty to the murder charge, she should have been charged with manslaughter entailing a much shorter sentence."

None of the newspaper articles dealing with the commutation actually provide the warden's name so it's frustrating that I can't positively identify which warden initiated the paperwork.

However, my money's on Dr. Frank L. Heacox.

Buffalo Evening New

(Mar 19, 1930)

Here's an Auburn Prison timeline for that period:

Edgar S. Jennings was the warden during the July 1929 and subsequent December 1929 riots, so it might have been to him that Marie reported the plot since the newspaper articles concerning the commutation request do not mention the December riots.

Edgar S. Jennnings resigned in January 1930.

John L. Hoffman replaced Jennings. However, Hoffman had a heart attack while in office and retired.

Hoffman was replaced by Dr. Frank L. Heacox on March 19, 1930. Heacox was the former chief physician and superintendent of Auburn's women's prison.

The fact that Heacox was on staff at the women's prison during the 1929 riots means Marie could have reported to him what she'd heard.

The signed decree stated that Marie needed to stay out of trouble, or risk being sent back to prison to serve out her sentence, and:

"...furthermore, that she will go to the State of Indiana to take care of her mother who is seriously ill and then return to the State of New York."

Presumably, once her sickly mother was dead.

.jpg) |

| Marie Strauss nee' Berlin is granted release from prison (Nov 17, 1930) |

Auburn's warden and New York's Governor Roosevelt were giving Marie Berlin a second chance.

Frances Berlin died in the town of Spencer, Indiana at 5 AM on November 25, 1935. Cause of death was "broncho-pneumonia." There was no autopsy. She had been under a doctor's care for pneumonia for the past 10 days. Frances's sister Mary Jarvis was listed as the informant on the death certificate.

It's curious that the informant wasn't Marie Berlin, since her freedom depended upon her acting as nursemaid to her mother.

Marie did not immediately return to New York, as was agreed upon five years earlier.

At what point Marie's life went off the rails, I can't say. After her mother's death, Marie began racking up arrests and convictions for narcotics-related crimes.

On March 9, 1937, Marie Berlin (then 48 yrs old) and a taxi driver named Oscar V. Spears (aged 63 yrs) were arrested together. Marie admitted to federal agents that it was she who had taken a blank prescription pad from the office of Dr. C.F. Pectol, a Spencer, Indiana physician.

Marie had been forging his name and having Spears purchase narcotics for her. Investigators found a quantity of morphine and morphine derivatives.

Marie was bound over to the Federal Grand Jury on a charge of forging narcotic prescriptions and she was committed to the Marion County Jail in default of a $2,000 bond.

I'm not sure what punishment might have been imposed on Oscar Spears. Perhaps once Marie confessed to being the forger, he was let off with a warning?

Marie's penalty for her crime was revealed in the Indianapolis Star newspaper on March 20,1937:

"Miss Marie Berlin, a comely Spencer young woman, pleaded with Judge Baltzell to give her a minimum sentence on her plea of guilty for forging narcotic prescriptions, but the judge gave her a year and a day in prison.

Judge Baltzell said that length of time would be sufficient to cure her of the drug habit."

I don't know about that, Judge.

On July 13, 1939, in a Portsmouth, Ohio apartment, Marie Berlin (now 51 yrs old) was arrested, along with Cecelia Rhoads (41) and her husband, Samuel Rhoads (51).

All three inhabitants of 1748 12th Street were charged with illegal possession of narcotics. Detectives found 50 grains of morphine and assorted drug paraphenalia, including 12 hypodermic needles. They also found eight forged prescriptions in the apartment, none of which were signed by a local physician.

Police were acting on a complaint about the trio which stated the women never left the apartment and Samuel didn't not go out until nightfall.

Both Samuel of Cecelia Rhoads had prior convictions for forging prescriptions, stemming from arrests made on the west coast.

The July 13, 1939 arrests were the result of a coordinated effort between Cincinnati Detective Ray Brown; federal narcotics officer George J. Gray, who was in charge of Cincinnati's federal division; and Ralph H. Oyler, a federal supervisor from Detroit.

According to reports, the trio moved from city to city to evade apprehension, staying at each location for three of four weeks. They'd been in Portsmouth for a month, prior to that they'd resided in Dayton, Ohio.

All three were placed under a $2,500 bond each, an impossible sum for any of them to pay. They were committed to the Columbus city prison to await trial.

A federal grand jury indicted Marie and Cecelia on a charge of forging narcotics subscriptions.

Cecelia was arrested on a separate charge while in custody when it was discovered, on July 18th, that she had obtained 4 morphine tablets while incarcerated. Cecelia claimed innocence.

Ultimately, both Marie and Cecelia plead guilty and they were each sentenced to two years in a federal penitentiary.

Samuel was indicted on a charge of purchasing untaxed narcotics. He was accused of purchasing 15 1/2 grains of morphine on July 13th.

Samuel denied his guilt and went to trial. Cecelia had testified on his behalf at the trial, claiming the drugs belonged to her.

The jury was out for 15 minutes on November 6, 1939 before returning a guilty verdict. Samuel would claim he'd been "convicted on false evidence." He too was ordered to serve a term of two years in a federal penitentiary.

Samuel Rhoads spent the next two years as prisoner 5282 at the US Public Health Service Hospital (USPHS) in Lexington, Kentucky.

Opened in 1935, the hospital (more commonly referred to as The Narcotic Farm or Narco) was a combination prison, treatment facility, research institution and working farm. All prisoners or patients were battling addiction.

The 1940 census lists both Cecelia and Marie as inmates at Federal Reformatory for Women aka Alderson Federal Prison Camp, in Monroe County, West Virginia.

While we can never forget Marie Berlin beat her friend to death in November 1919, she did eventually get her life back on track.

The same can not be said for her drug-addicted cohorts, Mr. and Mrs. Rhoads. I'll deviate for a bit and review their continual brushes with the law before circling back to Marie Berlin.

In February 1942, Cecelia Rhoads was arrested in Dayton, Ohio for (once again) presenting a forged prescription to a drug store. The forged name was "Dr. John F. Torrence, of Germantown" the pharmacy was Gallaher Drug Store, located at Fourth and Main Street in Dayton.

Cecelia Rhoads was charged with "fraudulently executing narcotic prescription and uttering same."

Unable to furnish the $1,000 bond, Cecelia was committed to the Clark County Jail, to await a grand jury ruling. Cecelia was indicted in May 1942 and she plead guilty. In July 1942, Cecelia received two 2 year sentences, to run concurrently, both suspended.

When 54-year-old Samuel Rhoads registered for the draft on April 28, 1942, he was employed by the Williams Soft Drink Corp in Cincinnati, Ohio.

On February 21, 1945, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Cecelia Rhoads and Louis George Ernst, a 24-year-old taxicab driver, each entered a not guilty plea to charges of acquiring and possessing 12 grains of opium. Bond was set at $500.

It was reported that Cecelia was "well-dressed and said she had once been a schoolteacher."

Cecelia requested that she be granted medical care at the USPHS, Federal Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky while awaiting dispositon of her case. (The Narcotic Farm was not an option for women until 1941.)

At a February 27, 1945 hearing regarding the charges, Cecelia Rhoads changed her plea to guilty. The change of heart came after listening to testimony given by city detective, Henry Bader.

Bader testified that he and federal narcotics agents had trailed Cecelia and Ernst on a tour of 15 drugstores in the eastern part of Cincinnati. Bader had observed that at several of those drugstores, Ernst, without his driver's cap, and having given an assumed name to the pharmacists, had purchased paregoric for Mrs. Rhoads. Paregoric contains two grains of opium to the ounce.

W.V. McDonald, a federal narcotics agent, said that more than 150 empty paregoric bottles were found at the home of Mrs. Rhoads (506 Broadway). The bottles are small but that still seems like a lot of bottles.

Samuel Rhoads had also been swept up in the drama and he was arrested on a state charge of possession of a hypodermic needle.

At the time Cecelia was pleading guilty to these new (yet familiar) charges, The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that Mrs. Rhoads had been arrested nine times in the last 15 years on narcotics charges, several times as Cecelia Hubby, in San Francisco, Denver and Columbus, Ohio.

Louis George Ernst was dismissed with a warning.

I can't find a further report on Cecelia's punishment for the paregoric/opium charge or any prison time for Samuel for the drug paraphenalia charge but wherever Cecelia ended up, she didn't stay there long enough to kick the habit.

By 1950 (using the U.S. census as a source), Marie Berlin was in a better place than other Cecelia or Samuel Rhoads.

In March 1950, Cecelia had been found guilty of "habitual use of narcotics."

unidentified inmate of USPHS,

LEO Weekly photo

Cecelia received a rather light sentence, considering her history; one year of probation, on the condition that she enter the USPHS. And this is where we find her in the 1950 census (enumerated in May 1950). Cecelia Rhoads was once again a patient at The Narcotic Farm in Lexington, KY.

While it was true that some USPHS patients who were seeking treatment had entered the hospital voluntary, Cecelia was certainly not one of them. Many of the USPHS patients had either arrived either as transfers from federal prisons or they'd been sent there following a conviction for violating narcotics laws. The facility had a consistently high relapse rate (roughly 90%).

The 1950 census lists Samuel Rhoads as residing at a Veteran's Admininstation Facility in Dayton, Ohio. Samuel had served in the Army during WWI, with the 144th Machine Gun Battalion, from June 25, 1918 to May 4, 1919. The census indicates Samuel is "unable" to work.

As I'd stated earlier, Marie Berlin, it would seem had eventually gotten her self straight.

The 1950 census indicates Marie was living in a Stuyvesant Place apartment building on Staten Island and working as a librarian at "City Hospital." I do wonder if this is some non-specific hospital in Manhattan or the "City Hospital" located on Welfare Island (now Roosevelt Island).

City Hospital on Welfare Island

It's odd to think that someone with multiple federal narcotics convictions could find employment at a hospital but I suppose if she restricted her movements to the library, she could be trusted.

Marie Berlin died on July 8, 1964. She was 76-years-old. Marie's body was shipped from Staten Island, NY to Spencer, Indiana. She's buried with her parents and two sisters in the Berlin family plot in the Riverside Cemetery.

Findagrave.com upload by John Maxwell

In the interest of general housekeeping:

Background information for Clara Branch has been sparse. I probably could have posted this story a lot sooner if not for my continued efforts to learn more about the victim. I suspect that even though I've drawn a line through this story, I'll keep looking for clues as to Clara Branch's background.

I'll share what I know:

The paperwork I purchased from the Fresh Pond Crematory lists Clara's age is "41," her marital status is "married" and that's the extent of the background information for Clara Branch made available by the Crematory. Not really the best use of $36.00 but if I hadn't spent the money, I would have been left wondering what information the crematory had on Clara. Unfortuantely, as her body was being committed to the flames, there were no mourners. Nor is there a name of someone who may have claimed her ashes; just a reminder to the undertaker, Wm. B.T. Reynolds, that "Ashes kept ten days free, after which our charges are one dollar per month."

Clara Branch's death certificate, recently obtained by me (in person for $22.00 plus parking fees), doesn't provide much in the way of clues either.

Henry Wright was the informant for Clara's death certificate and he could only tell them what he knew of Clara's past. Clara's parents names are "unknown." Her husband's christian name is "unknown." Clara's birthdate is "unknown." Clara's marital status is "widowed" - this contradicts previous reports of Clara being married but separated. Clara's birthplace is listed as "Louisville, KY." This was a solid clue but without knowing Clara's maiden name, date of birth or parent's names, I was still left scratching my head.

Greater detail was supplied concerning Clara's manner of death:

"Hemorrhage, from numerous fractures of the skull, hammer blows inflicted with homicidal intent."

Had any newspaper or document revealed the names of Clara's parents or her erstwhile husband, researching Mrs. Clara Branch would have been much easier.

I was only able to locate a Clara Branch on the New York State census from June 1915. Unfortunately, there isn't much in the way of biographical information for people who participated in that year's NYS census. There is no space for an individual's marital status, number of children born to the women or even birthplace, just "nativity."

But, if the 1915 Clara Branch if the same Clara Branch who was killed 3 1/2 years later, this single document may provide a connection between Clara and her killer.

Naturally, because I'm relying solely on this paperwork for clues, whoever jotted down the information (in cursive) made an error and then a correction by writing over their mistake with an even heavier pen stroke.

Sharing a Hempstead, New York abode in 1915, we find three women - Clara Branch (36-years-old, no occupation and listed as "head of house"), her 35-year-old "sister" and a 23-year-old "friend."

Clara's friend, Nellie Shultz," is a "saleslady" but her sister is identified as being in "show business."

As you can see, the sister's last name was intially recorded as "Branch." The enumerator then wrote over his mistake. In fairness, Liquid Paper wasn't created until 1960. Wite-Out came six years after that.

![]()

Clara Branch in the 1915 NYS Census

Ancestry.com interprets the handwriting as "Margarette Stull." I'm seeing the sister's first name as "Margurette." And is the last name "Still," "Stull," or "Stuhl?"

But is "Stull" the sister's maiden or married name? Although the US census began recorded an individual's marital status as early as 1880 - this is the New York State census and no such questions were being asked. I've tried searching under an assortment of alternate spellings of both her first and last name but I haven't hit paydirt.

If Clara's sister was involved in show business, perhaps this is how Clara made the acquaintance of Marie Berlin, one-time wife of vaudevillian performer Leo Strauss aka Fred Warren. Granted, there's no clarification as to what area of "show business" Margarette was involved in but still .... both Marie and Margarette had ties to that world.

If this is the same Clara Branch, where was Margarette in the wake of her sister's murder? Why didn't she claim the ashes or speak to the press?

The New York Times reported on

November 17, 1919: "It was learned that Mrs. Branch carried about $2,000

in life insurance, but in none of the policies found was a beneficiary

named." I find that odd, in and of itself.

The only other possible connection between Clara Branch and Marie Berlin is Louisville, Kentucky.

Henry Wright said Clara Branch was born there and Louisville is where Marie Berlin and Leo Strauss were married (February 1910). Louisville is located right near the Indiana border. The Berlin family lived in Marion County, Indiana. That is roughly 2 1/2 hour drive now, I don't know what it would have been like in the early 20th century.

Or are the two women friends as a result of Marie's earlier morphine addiction?

If you recall, The Brooklyn Eagle reported that "Mrs. May Smith, Mrs Warren's friend, is expected to make important disclosures in the relations of the clique of which Mrs. Warren and her victim were alleged members."

There really is no way for me to know and I don't like to speculate.

Captain Henry Wright did not return to live at the house he'd shared with Clara Branch nor did he return to his wife, Adelia.

Henry's address at that time Clara's death certificate was issued was the Queenswater Hotel in Long Beach.

Subsequent US census records (1920, 1930 & 1940) show Henry Wright as a boarder in the home of Mrs. Margaret Berry at 8 Lawrence Street in East Rockaway, NY.

In 1950, Margaret Berry is living with Henrietta Wright, the widow of Capt. Henry Wright's brother Edward, who had died on May 5, 1947.

I've not been able to find a date of death for Captain Henry Wright. With only the US census records to guide me, it's likely Capt. Wright (born 1865) died some time after May 1, 1940 and before April 1950.

Henry's wife, Adelia Wright nee' Langdon died on April 21, 1948. She was 85-years-old.

As I stated earlier, Marie Berlin's former husband Leo Strauss died on January 2, 1917, when he was 56 years old.

Butte Daily Post

May 17, 1916

Leo's stage partner Al Blanchard had died two years earlier - on September 18, 1915.

In the time between Blanchard's death and his own, Leo had paired with a man named Dietrick and they continued their career(s) in vaudeville.

Leo's third and last wife, Wally Warren died, at the age of 62 years, on February 19, 1951.

Charles R. Weeks, the Nassau County District Attorney in charge of Marie Berlin's case, transitioned from District Attorney to defense lawyer after leaving office in 1925. Among his clients was Frank "Two Gun" Crowley. Charles R. Weeks died on July 5, 1948 following a long illness. According to his obituary in Newsday: Weeks had been in ill health since a sudden attack of bronchial asthma in 1946. He was 72-years-old.

Marie Berlin's attorney Charles N. Wysong died on June 28, 1954, at the age of 73.

Two years after obtaining Marie Warren's confession, Detective Carman Plant was accused of accepting bribes. Plant was convicted on July 28, 1921 of receiving stolen property (specifically motor cars) and he was sentenced to serve two to five years in Sing Sing Prison. Plant entered the prison on August 3, 1921 and he was released on parole on November 28, 1922.

No longer able to work as a detective for the District Attorney, Plant found employment as a watchman on the Long Island Railroad crossings.

NYS Governor Alfred E. Smith approved Plant's "Restoration to Citizenship" (considered a "partial pardon") on June 9, 1924. Carman Plant died on December 13, 1936. He was 61-years-old.

|

| Ray Barbuti, 1928 |

In 1925, Barbuti, an Italian immigrant, found work as the official Italian interpreter for the Nasau County Court. He held this position until his death. Thomas V. Barbuti died on January 25, 1933 at the age of 57. He'd been battling pneumonia for 10 days prior to his death.

Of interest is the fact that Thomas's son Ray Barbuti competed in the 1928 Summer Olympics and won 2 gold medals for running.

In a surprising development, respected criminologist and Nassau County's fingerprint expert, Deputy Sheriff Charles W. Hansen was fired from his job in June 1923.

According to the New York Daily News: "Hansen was of indicted on a charge of accepting money to settle an automobile accident case while an official of the county of Nassau. His defense was that he engaged two men to make an investigation of the accident in which a friend of his was injured. He denied that he kept the money."

Charles W. Hansen was found guilty of extortion and accepting bribes. The guilty verdict was handed down on November 21, 1923 and Hansen received a suspended sentence.

circa 1919

"They have taken from me that which I hold dearest in this world, my good name," Hansen said. "This is outrageous justice." Hansen vowed to fight the conviction but he moved on with his life; he founded the American Confidential Bureau, headquartered in Manhattan.

Hansen's formal appeal was rejected on December 5, 1924 by an appellate court and the verdict was upheld. However, on January 21, 1926, Governor Alfred E. Smith signed off on paperwork requesting the Secretary of State issue a pardon to Charles W. Hansen.

The thrice-wed Charles W. Hansen died on May 31, 1954, in Los Angeles, California. He was 55-years-old.

Aaron Hoffman, the playwright who figured heavily in Marie Berlin's alibi, died, at his home, on May 27, 1924. He was 44-years-old. The New York Daily News attributed his death to "...heart disease. He had been ill for several months."

Catherine Hayes died, I believe, in 1941. She would have been 55-years-old. Her old vaudeville partner and sister Sabel Johnson Dunn died on January 5, 1946. Sabel was 58-years-old.

|

| findagrave upload by Barbara Wineinger |

Samuel James Rhoads died on October 28, 1958, in Kern, California. He was 70-years-old. He is buried in Union Cemetery in Barkersfield, California.

And what of Sarah Files, who once occupied the cell next to Marie Berlin? Sarah Files, 23-years-old and single, had been arrested and charged with the murdering her nine-day-old child (newspapers don't bother to specifiy the child's gender).

On October 30, 1919, Henry Lamb and Albert Pfeiefer were driving by the Old Westbury Pond when they spotted a small body floating in the water. Half an hour later, Constable Charles O'Connor arrested Sarah Files. She quickly broke down and admitted her guilt.

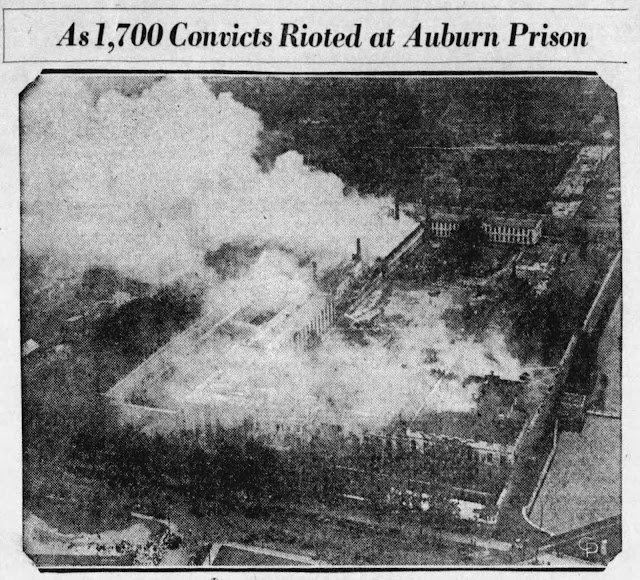

Sarah claimed Irving Davis, a soldier at Camp Albert L. Mills had betrayed her.

Sarah, desperate and not knowing what to do with her newborn child, tossed the baby into the pond.

Sarah Files was found guilty of "1st degree manslaughter" and checked into Auburn Prison on March 22, 1920. She was paroled on December 27, 1922 and discharged on January 21, 1924. It's not inconceivable that this is the same 28-year-old Sarah Files who died in Manhattan on August 22, 1924.

Lexington's Narcotic Farm, where both Samuel and Cecelia Rhoads spent time, treated several famous people in it's 40 years of operation, including William S. Burroughs, Sonny Rollins, Chet Baker and Peter Lorre.

If celebrity addicts don't interest you, you might want to delve into the Farm's questionable research studies, including its involvement in Project MKUltra.

There's plenty of additional reading available with regards to The Narcotic Farm, including a 2008 book co-authored by Nancy D. Campbell called "The Narcotic Farm: The Rise and Fall of America's First Prison of Drug Addicts."

If you'd rather something more visual, there are some very informative videos on YouTube about The Narcotic Farm. I'll recommend this YT video - https://youtu.be/u0c8xrT9RrI.

The video is short enough to watch if you're pressed for time but it's rather informative because it's a Kentucky Historical Society production.

If you've got more time to spare, check out "The Narcotic Farm," a 2008, 55 minute documentary produced by Nancy D. Campbell's co-authors, J.P. Olsen and Luke Walden. Here's a link to watch it on Vimeo - https://vimeo.com/91392115

If podcasts are more your thing - you may want to listen to episode 40 of Jessie Bartholomew's Kentucky History & Haunts. You can search for it wherever you find your podcasts or here's a link - https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/jessie-bartholomew/episodes/39--Narcotic-Farm--Lexington-ev04i9/a-a58pgdl

I'm also going to recommend podcast episode 2 of Tea Time Crimes - it concerns the murder of Julia Wilkins.

If you recall, it was Marie Berlin's attorney Charles N. Wysong who had defended Julia's husband in the trial.

Again, it's available wherever you get your podcasts but here's a link - https://lnns.co/NKmt8PkWoAg

One final item of interest - True Detective Mysteries magazine carried an article on the murder of Clara Branch in their July 1928 issue. Written by Arthur Mefford, it was titled "Blood on a Suede Handbag."

It's was in that article that I found the illustration of Catherine Hayes (called "Lily Dimix" in the story) surrendering evidence to the detective investigating the case.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)